A 21st Century

Movement

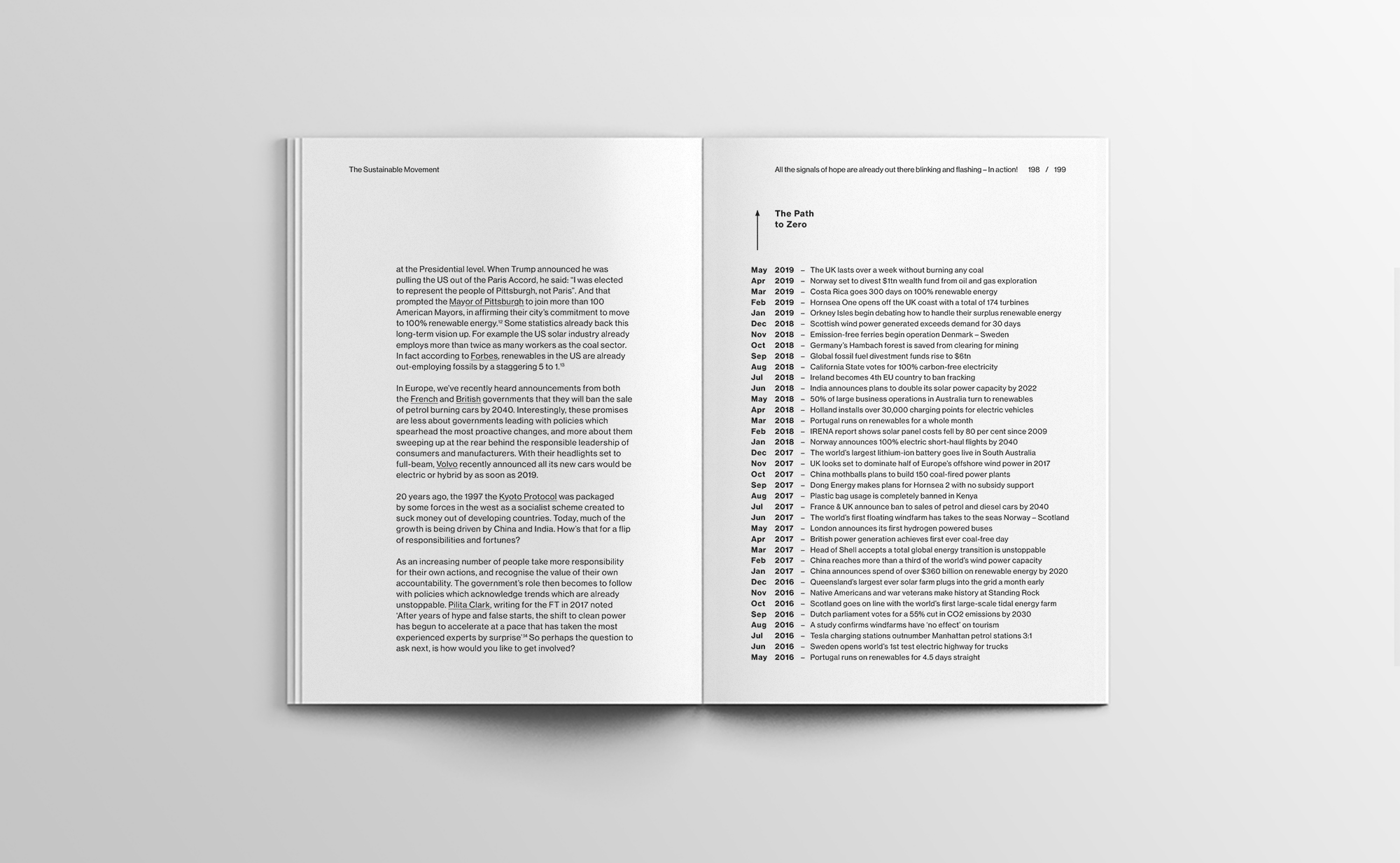

All the Signals of Hope Are Already Out There Blinking and Flashing —In Action!

‘It is as if every county in the world woke up one bright morning to find it had a North Sea at its disposal’.

—

Kingsmill Bond – New Energy Analyst

—

Kingsmill Bond – New Energy Analyst

As you read these words, the world is adding more capacity for renewable energy than fossil fuels. Unlike reserves of oil, coal or gas, every nation has a healthy combination of the wind and the sun. In fact, the sun supplies enough energy in just one hour to meet all the world’s energy needs for an entire year.1 Meanwhile the wind blowing outside your front door once originated from somewhere in the middle of the ocean, and constitutes sufficient natural energy to power the planet some 50 times over.2 If only a little more of it could be harvested effectively.

To look at the planet’s natural energy systems a different way – since the very beginning of life on Earth, all our food’s growth has been powered by the sun and fed by the rain. Likewise our best decarbonisation technology (otherwise known as trees), already turns carbon very effectively into oxygen by using the sun’s natural light. We use these free sources of energy every single minute of every single day, in ways we don’t necessarily always see.

Sometimes we can be guilty of polarising our thinking and viewing natural world and technology as opposites, when in fact some of our best innovation stories have involved the mutual dependence of the two. Water falls from the sky and therefore is an invention of nature, yet it feeds our fields through irrigation channels which are an invention of humankind. It is here, right from the sweet spot between the two that have always sprung our most sustainable solutions.

When too much emphasis is placed on human needs, we can be prone to neglect the natural environment around us. Yet not so long ago, a balance of reverse proportions meant humans were regularly getting beaten up by nature instead. Moving forward, the future lies somewhere in this fertile middle area, where we use our imagination to allow both nature and ourselves to thrive simultaneously.

The compelling reasons to switch to cleaner forms of energy extend way beyond the climate change debate. Fairness and pollution reduction also come into play, as Rahwa Ghirmatzion from PUSH Buffalo points out: ‘We’ve seen that even Americans who don’t “believe” in climate change are embracing renewable energy. Some of them value cleaner air, others value energy independence and national security, and others are called to care for creation.’3 Then of course, there are also the increasingly inarguable economic benefits. So much so that even some of the oil companies themselves claim to be divesting their activity and money away from fossil fuels.

In the USA, incentives like Obama’s carbon pricing models might be a thing of the past, but the cost of renewable energy is still tumbling faster than widely understood. This might go some way to explain why cuts to government subsidies are no longer affecting market growth.

In the decade since 2009, the cost of wind turbines fell by nearly a third, and solar panels plummeted by as much as 80%.4 Households and businesses that own their own premises have woken up to realise they can change the way they generate their energy faster than the providers. It was trends like these that made the Paris Agreement in 2015 possible. As Christiana Figueres, a former UN climate official observes: ‘Switching away from coal no longer looked impossible, even in developing countries.’5

Serendipity, too, plays its own role. For example, the once oil-heavy state of Texas now has more installed wind power capacity than Canada and Australia combined. These turbine fields sprang from a happy accident where carbon pricing bumped fists with a high-capacity power line, built originally to power all the pump jacks which once sucked 800 million barrels of oil from the Permian Basin.6 From there, the decision to adapt to natural power was a financial no-brainer. In 2008, the turbines in Texas helped America briefly pip Germany and China as the world’s leading producer of power from the wind. If Texas were a country, it would rank as the world’s fourth largest wind power provider.7

Recycling existing infrastructure like this opens a powerful treasure chest of possibilities to reinvent the human-made landscape, help fully decarbonise our economies, and introduce more sustainable methods of living. On a small but repeatable scale, individual buildings can now produce more energy than they consume. Whilst they take from nature on the ground, modern techniques help give back to nature on their roofs. In Japan golf courses built during the electronics boom of the 1980s are being repurposed as solar farms. Their primarily south-facing slopes, once host to important business deals, lend themselves perfectly to the application of clean-energy-making solar panels.8 In Australia, an old zinc mine is being converted to store electricity in the form of compressed air. And in the North Sea, plans are under way to store carbon captured from Dutch ports in empty gas fields.

The transformation of old industrial buildings into revitalised hubs for community and culture also serves as strong emblems for what is possible. In previous lives both the Tate Modern in London and the recently renovated MAAT building in Lisbon, were once coal-burning power stations belching toxic pillows of smoke. Today, through their world-class art exhibitions, these inspirational spaces help power our imagination and fresh thinking instead.

Improved access to culture means that more mindful ways of thinking are breaking out of their niche grooves and making their way into the mainstream. A recent Netflix documentary called ‘Minimalism’ showcased a positive trend for asking much deeper questions about what our possessions mean to us as individuals. This suggests a shift in the wider conversation, where the brands that once dominated our perceptions of ownership, now increasingly struggle to define in advance what our purchases symbolise.

Today, even the concept of materialism is being redefined by a new wave of minimalist thinkers who some are calling the ‘true materialists.’ They see our relationship with goods as defined less by what they symbolise outwardly and more by what their use and value means to us – the owner. These hybrid perceptions of value include the ethics and principles of the materials which our products are made from. At the deeper metaphysical level, the movement aims to identify ‘how matter comes to matter.’9 Even basic ideas of ownership are being challenged – from the popularity of open source frameworks, to carpooling schemes that make the ‘ride share brands’ more recognisable than the cars used – proving the things we share can hold equal value to the things we physically own.

Outside of the factors we can control, the take-up of clean energy systems worldwide is assuming different patterns in different places due to a huge number of variables. We’ve already discovered in Germany that the taxpayer largely bankrolled their ‘Energiewende’, or green energy revolution.

Meanwhile in Australia, with little or no help from the government, the simple mix of plentiful sunshine and rising utility costs is causing homes to switch to generating their own power. With battery companies flocking to Australia, people are shifting from ‘consumer’ to ‘prosumer at such a rate that the conventional grid may soon be a thing of the past.10 So much so, developments such as this are giving traditional power companies cause for concern.

Back in earthquake-prone Japan, seismic activity deep underground has long influenced the makeup of life above it. Architectural styles have always been dictated by the need to be light, flexible, and in the event of the ground shaking, easily repairable. These same geological factors are presently exerting their influence over how the Japanese make, store and consume electricity. The Fukushima disaster in 2011 amplified the public desire to seek an alternative future which would be more flexible, reliable, and sustainable. In 2016 a powerful earthquake shook the southern city of Kumamoto. Cut off from the grid, the town was left in darkness for almost a week, yet the lights stayed on in at least 20 homes with solar-storage units.11

Over in the US, democratically elected leaders at state level, fortunately maintain more influence over their communities’ energy sources and distribution, than the decisions made at the presidential level. When Trump announced he was pulling the US out of the Paris Accord, he said: ‘I was elected to represent the people of Pittsburgh, not Paris.’ And that prompted the mayor of Pittsburgh to join more than 100 other American mayors in affirming their cities’ commitment to move to 100% renewable energy.12 Some statistics already back this long-term vision up. For example the US solar industry already employs more than twice as many workers as the coal sector. In fact according to Forbes, renewables in the US are already out-employing fossils by a staggering five to one.13

In Europe, we’ve recently heard announcements from both the French and British governments that they will ban the sale of petrol-burning cars by 2040. Interestingly, these promises are less about governments leading with policies that spearhead the most innovative of changes, and more about them sweeping up at the rear behind the more responsible leadership of some manufacturers.

Twenty years ago, the 1997 Kyoto Protocol was repackaged by some forces in the West as a socialist scheme created to suck money out of developing countries. Today, much of the growth is being driven by China and India. How’s that for a flip of responsibilities and fortunes?

As an increasing number of people take more responsibility for their own actions, and recognise the value of their own accountability. The government’s role then becomes to follow with policies which acknowledge trends that are already unstoppable. Pilita Clark, writing for the Financial Times in 2017 noted: ‘After years of hype and false starts, the shift to clean power has begun to accelerate at a pace that has taken the most experienced experts by surprise.’14 So perhaps the question to ask next is: How would you like to get involved?

To look at the planet’s natural energy systems a different way – since the very beginning of life on Earth, all our food’s growth has been powered by the sun and fed by the rain. Likewise our best decarbonisation technology (otherwise known as trees), already turns carbon very effectively into oxygen by using the sun’s natural light. We use these free sources of energy every single minute of every single day, in ways we don’t necessarily always see.

Sometimes we can be guilty of polarising our thinking and viewing natural world and technology as opposites, when in fact some of our best innovation stories have involved the mutual dependence of the two. Water falls from the sky and therefore is an invention of nature, yet it feeds our fields through irrigation channels which are an invention of humankind. It is here, right from the sweet spot between the two that have always sprung our most sustainable solutions.

When too much emphasis is placed on human needs, we can be prone to neglect the natural environment around us. Yet not so long ago, a balance of reverse proportions meant humans were regularly getting beaten up by nature instead. Moving forward, the future lies somewhere in this fertile middle area, where we use our imagination to allow both nature and ourselves to thrive simultaneously.

The compelling reasons to switch to cleaner forms of energy extend way beyond the climate change debate. Fairness and pollution reduction also come into play, as Rahwa Ghirmatzion from PUSH Buffalo points out: ‘We’ve seen that even Americans who don’t “believe” in climate change are embracing renewable energy. Some of them value cleaner air, others value energy independence and national security, and others are called to care for creation.’3 Then of course, there are also the increasingly inarguable economic benefits. So much so that even some of the oil companies themselves claim to be divesting their activity and money away from fossil fuels.

In the USA, incentives like Obama’s carbon pricing models might be a thing of the past, but the cost of renewable energy is still tumbling faster than widely understood. This might go some way to explain why cuts to government subsidies are no longer affecting market growth.

In the decade since 2009, the cost of wind turbines fell by nearly a third, and solar panels plummeted by as much as 80%.4 Households and businesses that own their own premises have woken up to realise they can change the way they generate their energy faster than the providers. It was trends like these that made the Paris Agreement in 2015 possible. As Christiana Figueres, a former UN climate official observes: ‘Switching away from coal no longer looked impossible, even in developing countries.’5

Serendipity, too, plays its own role. For example, the once oil-heavy state of Texas now has more installed wind power capacity than Canada and Australia combined. These turbine fields sprang from a happy accident where carbon pricing bumped fists with a high-capacity power line, built originally to power all the pump jacks which once sucked 800 million barrels of oil from the Permian Basin.6 From there, the decision to adapt to natural power was a financial no-brainer. In 2008, the turbines in Texas helped America briefly pip Germany and China as the world’s leading producer of power from the wind. If Texas were a country, it would rank as the world’s fourth largest wind power provider.7

Recycling existing infrastructure like this opens a powerful treasure chest of possibilities to reinvent the human-made landscape, help fully decarbonise our economies, and introduce more sustainable methods of living. On a small but repeatable scale, individual buildings can now produce more energy than they consume. Whilst they take from nature on the ground, modern techniques help give back to nature on their roofs. In Japan golf courses built during the electronics boom of the 1980s are being repurposed as solar farms. Their primarily south-facing slopes, once host to important business deals, lend themselves perfectly to the application of clean-energy-making solar panels.8 In Australia, an old zinc mine is being converted to store electricity in the form of compressed air. And in the North Sea, plans are under way to store carbon captured from Dutch ports in empty gas fields.

The transformation of old industrial buildings into revitalised hubs for community and culture also serves as strong emblems for what is possible. In previous lives both the Tate Modern in London and the recently renovated MAAT building in Lisbon, were once coal-burning power stations belching toxic pillows of smoke. Today, through their world-class art exhibitions, these inspirational spaces help power our imagination and fresh thinking instead.

Improved access to culture means that more mindful ways of thinking are breaking out of their niche grooves and making their way into the mainstream. A recent Netflix documentary called ‘Minimalism’ showcased a positive trend for asking much deeper questions about what our possessions mean to us as individuals. This suggests a shift in the wider conversation, where the brands that once dominated our perceptions of ownership, now increasingly struggle to define in advance what our purchases symbolise.

Today, even the concept of materialism is being redefined by a new wave of minimalist thinkers who some are calling the ‘true materialists.’ They see our relationship with goods as defined less by what they symbolise outwardly and more by what their use and value means to us – the owner. These hybrid perceptions of value include the ethics and principles of the materials which our products are made from. At the deeper metaphysical level, the movement aims to identify ‘how matter comes to matter.’9 Even basic ideas of ownership are being challenged – from the popularity of open source frameworks, to carpooling schemes that make the ‘ride share brands’ more recognisable than the cars used – proving the things we share can hold equal value to the things we physically own.

Outside of the factors we can control, the take-up of clean energy systems worldwide is assuming different patterns in different places due to a huge number of variables. We’ve already discovered in Germany that the taxpayer largely bankrolled their ‘Energiewende’, or green energy revolution.

Meanwhile in Australia, with little or no help from the government, the simple mix of plentiful sunshine and rising utility costs is causing homes to switch to generating their own power. With battery companies flocking to Australia, people are shifting from ‘consumer’ to ‘prosumer at such a rate that the conventional grid may soon be a thing of the past.10 So much so, developments such as this are giving traditional power companies cause for concern.

Back in earthquake-prone Japan, seismic activity deep underground has long influenced the makeup of life above it. Architectural styles have always been dictated by the need to be light, flexible, and in the event of the ground shaking, easily repairable. These same geological factors are presently exerting their influence over how the Japanese make, store and consume electricity. The Fukushima disaster in 2011 amplified the public desire to seek an alternative future which would be more flexible, reliable, and sustainable. In 2016 a powerful earthquake shook the southern city of Kumamoto. Cut off from the grid, the town was left in darkness for almost a week, yet the lights stayed on in at least 20 homes with solar-storage units.11

Over in the US, democratically elected leaders at state level, fortunately maintain more influence over their communities’ energy sources and distribution, than the decisions made at the presidential level. When Trump announced he was pulling the US out of the Paris Accord, he said: ‘I was elected to represent the people of Pittsburgh, not Paris.’ And that prompted the mayor of Pittsburgh to join more than 100 other American mayors in affirming their cities’ commitment to move to 100% renewable energy.12 Some statistics already back this long-term vision up. For example the US solar industry already employs more than twice as many workers as the coal sector. In fact according to Forbes, renewables in the US are already out-employing fossils by a staggering five to one.13

In Europe, we’ve recently heard announcements from both the French and British governments that they will ban the sale of petrol-burning cars by 2040. Interestingly, these promises are less about governments leading with policies that spearhead the most innovative of changes, and more about them sweeping up at the rear behind the more responsible leadership of some manufacturers.

Twenty years ago, the 1997 Kyoto Protocol was repackaged by some forces in the West as a socialist scheme created to suck money out of developing countries. Today, much of the growth is being driven by China and India. How’s that for a flip of responsibilities and fortunes?

As an increasing number of people take more responsibility for their own actions, and recognise the value of their own accountability. The government’s role then becomes to follow with policies which acknowledge trends that are already unstoppable. Pilita Clark, writing for the Financial Times in 2017 noted: ‘After years of hype and false starts, the shift to clean power has begun to accelerate at a pace that has taken the most experienced experts by surprise.’14 So perhaps the question to ask next is: How would you like to get involved?

—

Credits & Notes

1

World Energy Council

World Energy Resources 2013 Survey

‘Chapter 8 – Solar’

worldenergy.org (2013)

2

Ken Caldeira (Stanford University) cited by Paula Cocozza, ‘Wild is the wind:

the resource that could power the world’

The Guardian (15 Oct 2017)

3

Rahwa Ghirmatzion and Mark Ruffalo (PUSH Buffalo)

‘Clean energy is the future for America and the planet’

The Guardian (12 Aug 2017)

4

International Renewable Energy Agency

REthinking Energy

irena.org (2017)

5 / 11 / 14

Pilita Clark

‘The Big Green Bang:

How renewable energy became unstoppable’

Financial Times (May 18 2017)

6

Justin Rowlatt

‘Rattlesnakes, jackalope and a clean energy revolution’

Ethical Man Blog

BBC News (11 Mar 2009)

7

Powering Texas

(poweringtexas.com)

/ Wikipedia Page

‘Wind power in Texas’

wikipedia.org

8

Ariel Schwartz

‘Japan has finally figured out what to do with its abandoned golf courses’

Business Insider (16 Jul 2015)

9

‘How Matter Comes to Matter’

newmaterialism.eu

10

Simon Mouat

‘A New Paradigm for Utilities:

The Rise of the Prosumer’

Schnieder Electric Blog

blog.se.com (Nov 2016)

12

Lauren Gambino

‘Pittsburgh fires back’

The Guardian (1 Jun 2017)

13

Niall McCarthy

‘Solar Employs More People In U.S. Electricity Generation Than Oil, Coal And Gas Combined’

Forbes (Jan 25 2017)

Section 1 — Roots

Chapter 1 — An Introduction

Chapter 2 — The Rise and Fall of the Eclectics

Chapter 3 — The Bauhaus Function

Chapter 4 — De Stijl Meets Time

Chapter 5 — The Role of the Magazines

Chapter 6 — DADA

Chapter 7 — War. A Redfinition

Chapter 8 — The Ulm Age of Methods

Chapter 9 — Modernism and the Ongoing Project

Chapter 10 — Capitalism Eats Itself

Chapter 11 — Roughly Where We Stand Now

Interlude — Transition

Section 2 — Leaves

Chapter 12 — How Do Movements Happen?

Chapter 13 — Energy Makes Energy

Chapter 14 — Digital Need Not Be Digital

Chapter 15 — All the Signals of Hope...

Chapter 16 — Defining Sustainabilism

Chapter 17 — Sustainable by Design

Chapter 18 — The Future Will Take Us in Circles

Chapter 19 — Where Do We Go from Here?

Chapter 20 — The Role of the Arts

Chapter 21 — The Value in Meaning

Chapter 22 — Be More Tree

Chapter 23 — An Ending. A Beginning