A 21st Century

Movement

Capitalism Eats Itself

‘We shall hardly relinquish the shovel, which after all has many good points, but we are in need of a gentler and more objective criteria for its successful use’.

—

Aldo Leopold - A Sand County Almanac

—

Aldo Leopold - A Sand County Almanac

Just over a century ago, the very idea that people would one day be in touch with and examining their inner feelings would have been rejected as a ridiculous proposition. In 1914, the Habsburg court based in Vienna was still at the centre of a vast empire ruling a large portion of central Europe. Here, the notion of people, especially those holding all the power, sharing their true thoughts with each other, was seen not just as a sign of weakness, but as a threat to their absolute control.1

Socially, it simply wasn’t acceptable to talk about one’s own inner self. Forms of emotional suppression like this made the mass slaughter of WWI more possible, peaking in human costs with the Battle of Verdun, in which a French general by the name of Nivelle led several suicidal counter-attacks. This one battle alone lasted for 303 days, becoming one of the longest and most costly in human history, with close to one million human casualties. Men either side of the River Meuse did not question the duty being asked of them, and likewise their generals chose to not question the morality of their own orders. The devastating losses, propelled largely by fear, were repackaged by politicians and the media in a bullishly nationalistic guise.

Verdun had given the French a slogan – ‘ils ne passeront pas’ – but the victory was so costly to the nation’s spirit that some would argue, it has never completely recovered. The immediate capitulation of France in 1940 was partly because her people did not want to repeat Verdun ever again. The nation had awoken to its sense of self, and was now brave enough to collectively question.

During the four years which this First World War straddled, historian Norman Stone explains, the world effectively jumped from 1870 to 1940.2 In 1914 cavalry cantered off to stirring music, infantry charged with bayonets, and fortresses were built for long-lasting sieges. By 1918, French generals were employing methods of warfare involving tanks, infantry and aircraft more familiar to the German Blitzkrieg.

Meanwhile, some 7,000km away across the Atlantic Ocean, a new type of ruling class was emerging. America’s corporations came out of the conflict rich and powerful, their newly mechanised production lines still pouring out goods geared primarily to war. With victory secured, the new problem to solve was how to ensure continued demand. When people found themselves secure, with enough goods, would they cease buying? As the levels of production continued to rise, the goods made and the way they were sold needed to be adapted quickly.

One leading banker, Paul Mazur of the Lehman Brothers, had a clear vision of what was necessary: ‘We must shift America from a needs, to a desires culture... People must be trained to desire, to want new things even before the old has been entirely consumed. We must shape a new mentality in America. Man’s desires must overshadow his needs.’3

Whilst Gropius and his students at the Bauhaus were interrogating the purity and practical function of many household objects, the bankers and marketeers of Wall St were busy rejecting the marketing of a product’s practical virtues in favour of creating an impulse driven culture.

Sadly, due to a factor pivotal to this day, Gropius lacked the same scale of financial backing.

Beginning in the early 1920s, the New York banks funded the creation of a chain of department stores across North America. These were to be the outlets for the mass-produced goods. And according to the documentary maker Adam Curtis, ‘it was to become the advertiser’s job, led in no small part by a man by the name of Edward Bernays, who was to produce the new type of customer.’4

In 1927, an American journalist wrote ‘a change has come over our democracy, it is called consumptionism. The American citizen’s first importance to his country is no longer that of citizen, but that of consumer.’5 Corporations were dropping ideas where they thought of people in groups of one, and increasingly employing systems which thought of them in groups of thousands.

The stock market boomed. People were persuaded they could get rich simply by buying shares in the same corporations that had begun feeding their infinite desires. The movement was so powerful that in 1928, ‘President Hoover was the first politician to articulate the idea that consumerism had become the central motive of American life.’6 After his election he told a group of advertisers and public relations men: ‘You have taken over the job of creating desire, and have transformed people into constantly moving happiness machines. Machines which have become the key to economic progress.’7 The all-consuming self, like a cat purring contentedly full from a feed, was seen as happy and docile, thereby creating a stable society.

This new wave of consumerism was so unexpectedly powerful that an almighty stock market boom was followed by an inversely catastrophic crash. The slump intensified an already growing political, economic and political crisis which was emerging within the new democracies of Europe. Unemployment soared, and families were left bankrupt. In Germany and Austria, armed wings of rival political parties fought out their frustrations on the streets.

Two countries on different sides of the Atlantic again took very different paths out of the crisis. In March 1933 the National Socialists, led by Adolf Hitler, were elected to power in Germany, promising to abandon democracy because of the chaos and unemployment which the crash had caused. Meanwhile in America, Franklin D. Roosevelt took over and launched his New Deal in response to the Great Depression.

As well as financial reform, giant new industrial projects intended for the good of the nation were launched. The infrastructure projects his policies created didn’t just save democracy in the United States by preventing a second civil war; the new railroads, freeways and bridges also provided the means by which the goods of the capitalist economy could eventually spread and flow more efficiently.

As we stand poignantly at a similar fork in the road today, when the top level choices offered become only more binary, one overarching obligation that echoes is the need to save democracy itself. Here politicians and voters would be wise to embrace the brave plans and objectives of a Green New Deal which sprang into mainstream conversation in late 2018.

The Allied victory which ended WWII might have cemented the capitalist route forward that came to dominate the latter half of the 20th century. But it was the World’s Fair in 1939 that first celebrated the full bonding of design and architecture with the twins of consumerism and capital. Hosted in New York, the global expo heralded a future which looked and sounded a lot like utopia. Any doubts as to whether this was achievable were no match for the striking confidence of the heavily marketed scale models on display.

As Curtis explains, what was to come was a future where ‘it’s not that the people are in charge, its that the people’s desires are in charge.’8 Exhibition pieces such as ‘Democracity’ and General Motors’ ‘Futurama’, captured the world’s imagination because they presented a new era in which businesses ‘responded to the innermost desires in a way politicians could never do.’

Long-term stability relied on the promise that the future would always be better than the past. In fact capitalism’s longevity would come to depend on enough people continuing to believe this version of the future over any other. And this was perhaps capitalism’s greatest success. (It was also blessed to thrive through a century in which the world’s natural systems still had some ability to flex.)

A huge explosion in every form of mobility accelerated during the 1950s and 60s, successfully consolidating the 20th century as the age of mass transportation. The West was to be rebranded the ‘free world’, and America’s newly built arteries became known as ‘freeways.’ Capitalism, fuelled largely by the burning of oil, had set every individual free.

It’s worth us noting here that for any movement to succeed, Bob Hunter, co-founder of Greenpeace, will point you to the fundamental importance of storytelling: ‘You have to make a story which travels well. You have to create events which will impact on millions of people in every corner of the world. You have to create a truly global story. And you have to put on a good show.’9 If any movement throughout history has achieved excellence in this realm, then it would be Capitalism.

From the entertainment broadcast on television and radio sets in every family’s home, to the advertising piped directly to people’s neural nodes; from the floating of companies on the stock exchange, the showmanship and flurry of activity every day as the markets closed, to the feature films that further glamourised this lifestyle; from the magazines which promoted the films, to the cleverly placed products which the marketeers needed to sell. And now the social media networks and online retail giants, which through their intimate knowledge of what we already buy, keep bloating our desires with more of the same.

The greatest promo code anyone ever gave capitalism was communism. Like Loki to his brother Thor, communism became the nemesis or arch-rival which only compounded capitalism and made it stronger. During this era, becoming filthy rich became a respected profession in its own right.

During the 1980s Thatcher and Reagan exploited this tense standoff to create a lovechild of their own. Neoliberalism was to become a new ideology which would later work not just as capitalism's powerful defence shield, but also as a leach, draining the system dry from the inside out. Whilst capitalism was a set of social and financial practices whose aim was the accumulation of capital, neoliberalism was a set of beliefs which freed the way to maximise the profits of the capitalists by dismantling the last barriers that had been holding back unaccountable corporate power.

Privatisation, deregulation, the flouting of laws and taxes, the hollowing out of democracies, and the obstruction of green policies – these are all neoliberal trends we are more than familiar with, which together have hamstrung our ability to fight climate change, or plan for our future collective welfare.

Originally capitalism won all previous contests with its rivals, largely because it proved capable of elevating more people out of poverty and hardship than any of the alternatives. Continuing this trend of human alleviation is crucial to building a more sustainable future for the planet overall. Yet these days capitalism’s age is beginning to show, its increasingly worn-out mechanisms creaking ever louder over ever stormier seas, swelled and angered by its own far-reaching oars. Never before has its inner machine work been so transparent, or the darker secrets of its trade had so much scrutiny in the spotlight. As an organism, not only is it continuing to knowingly pollute ecosystems that it relies directly on for its own survival, but it is unapologetically taking from and breaking whole communities too. The ultimate consumer model has begun its final act, of ultimately consuming itself.

In 2010, the researcher Hans Rosling argued in one of his Ted talks, that carbon emissions and sustainable forms of development are intrinsically linked to population growth. A long-term sustainable future relies on us raising the living standards of the world’s poorest, so that we can begin to check population growth by 2050.10 Predictions, however, that on our current course an extra 1.2 million children in the UK alone will fall into poverty by 2030 holds deep irony, proving the capitalist system to which we’re still clinging is categorically no longer fit for purpose.

Thatcher helped set this course during the 1980s when she declared: ‘there is no such thing as society.’ She was of course spinning a pretty obvious falsity, but as we keep finding out to this day, a lie can be an equally effective invention as the truth, and in the hands of those with a tall enough pedestal to preach from, can still set a direction beyond mere discourse.

So the big capitalism truck continues to career down the road, increasingly out of control. There’s now fewer people in the front trying to steer it, and more in the back trying desperately to unload whatever remains of its precious cargo. Meanwhile, with the route still set to the pursuit of infinite growth, the juggernaut just keeps on going, swerving dangerously towards an increasingly perilous cliff-edge of climate (and social) breakdown.

Throughout history empires have fallen when from the outside perspective they have appeared to be at their strongest. From Ancient Rome and Greece to modern-day North America. What the glossy but thin external veneer hides is that they have grown hollow and become rotten from within. Collapsing-empire syndrome, otherwise known as ‘overstretch’, doesn’t just involve an underestimation of resources, but can also include an overreach of ambition and the imagination too. The historian Norman Foster defines this in more human terms as ‘the contest between pride and reality.’11

British journalist George Monbiot once described economic growth as ‘the fairy dust supposed to make all the bad stuff disappear.’12 Yet the fairytales which the capitalist system has been spinning are now so far stretched that they are unravelling at alarming speed. Capitalism will fail sooner or later, ultimately because it drives ecological destruction. It already fails to relieve structural unemployment or soaring inequality, the very things it once did so well – all moral purpose has been lost, whilst ‘the promise of growth is all that’s left.’

As the writer John Higgs explains: ‘If the system the world is run on is made of an imaginary currency underpinned by practices which ultimately harm the very thing we live on, then this system is ultimately on a timer to its own demise.’13 False concepts such as never-ending growth gain strength by surrounding themselves with ideology and elaborate commentaries, in the same way that, as Higgs says, ‘a pearl forms around a piece of grit in an oyster.’ The theory which surrounds any ‘ism’ functions like a ‘sophisticated defence mechanism which protects the central tenets from crashing and burning on the rocks of reality.’14 With a structure such as capitalism, more and more people are beginning to see through the shiny exterior, back to the small lump of dirt, still hidden somewhere in the middle.

This is all very worrying because modern-day economics and the perceived value of money is as much an ecosystem that we rely on for our peaceful prosperity as the daylight, sunshine and the rain. How do we change or reboot a system which we’re already wholly operating within? This is very much our present struggle.

Beginning to discredit some of the darker and more out of control capital flow systems would have only a net positive effect. For whilst carbon emissions remain a significant contributor to global warming, it is the murky world of financial corruption which hides amongst the root causes.15 Noam Chomsky offers an additional starting point when he says we must ‘move from creating structures and institutions which bring out the worst in us to the best.’

One century since capitalism first reigned supreme, today a new generation risks retreating once again into its own self-created empires. Our social media profiles, so carefully curated, they no longer reflect the reality of our daily lives, or more crucially represent how we truly feel. The Hungarian countess Erzie Károlyi said of the early 20th century, ‘to examine fully, with your eyes wide open the world around you, you would have put a lot of other things into question. Your society, everything that surrounds you, and that wasn’t a good thing at that time, because your self-created empire would have very much fallen to bits very much earlier already.’16 Here we are full circle, facing this unique challenge once again. If the jumper was on the wrong way round before, it's now also been turned inside out.

Socially, it simply wasn’t acceptable to talk about one’s own inner self. Forms of emotional suppression like this made the mass slaughter of WWI more possible, peaking in human costs with the Battle of Verdun, in which a French general by the name of Nivelle led several suicidal counter-attacks. This one battle alone lasted for 303 days, becoming one of the longest and most costly in human history, with close to one million human casualties. Men either side of the River Meuse did not question the duty being asked of them, and likewise their generals chose to not question the morality of their own orders. The devastating losses, propelled largely by fear, were repackaged by politicians and the media in a bullishly nationalistic guise.

Verdun had given the French a slogan – ‘ils ne passeront pas’ – but the victory was so costly to the nation’s spirit that some would argue, it has never completely recovered. The immediate capitulation of France in 1940 was partly because her people did not want to repeat Verdun ever again. The nation had awoken to its sense of self, and was now brave enough to collectively question.

During the four years which this First World War straddled, historian Norman Stone explains, the world effectively jumped from 1870 to 1940.2 In 1914 cavalry cantered off to stirring music, infantry charged with bayonets, and fortresses were built for long-lasting sieges. By 1918, French generals were employing methods of warfare involving tanks, infantry and aircraft more familiar to the German Blitzkrieg.

Meanwhile, some 7,000km away across the Atlantic Ocean, a new type of ruling class was emerging. America’s corporations came out of the conflict rich and powerful, their newly mechanised production lines still pouring out goods geared primarily to war. With victory secured, the new problem to solve was how to ensure continued demand. When people found themselves secure, with enough goods, would they cease buying? As the levels of production continued to rise, the goods made and the way they were sold needed to be adapted quickly.

One leading banker, Paul Mazur of the Lehman Brothers, had a clear vision of what was necessary: ‘We must shift America from a needs, to a desires culture... People must be trained to desire, to want new things even before the old has been entirely consumed. We must shape a new mentality in America. Man’s desires must overshadow his needs.’3

Whilst Gropius and his students at the Bauhaus were interrogating the purity and practical function of many household objects, the bankers and marketeers of Wall St were busy rejecting the marketing of a product’s practical virtues in favour of creating an impulse driven culture.

Sadly, due to a factor pivotal to this day, Gropius lacked the same scale of financial backing.

Beginning in the early 1920s, the New York banks funded the creation of a chain of department stores across North America. These were to be the outlets for the mass-produced goods. And according to the documentary maker Adam Curtis, ‘it was to become the advertiser’s job, led in no small part by a man by the name of Edward Bernays, who was to produce the new type of customer.’4

In 1927, an American journalist wrote ‘a change has come over our democracy, it is called consumptionism. The American citizen’s first importance to his country is no longer that of citizen, but that of consumer.’5 Corporations were dropping ideas where they thought of people in groups of one, and increasingly employing systems which thought of them in groups of thousands.

The stock market boomed. People were persuaded they could get rich simply by buying shares in the same corporations that had begun feeding their infinite desires. The movement was so powerful that in 1928, ‘President Hoover was the first politician to articulate the idea that consumerism had become the central motive of American life.’6 After his election he told a group of advertisers and public relations men: ‘You have taken over the job of creating desire, and have transformed people into constantly moving happiness machines. Machines which have become the key to economic progress.’7 The all-consuming self, like a cat purring contentedly full from a feed, was seen as happy and docile, thereby creating a stable society.

This new wave of consumerism was so unexpectedly powerful that an almighty stock market boom was followed by an inversely catastrophic crash. The slump intensified an already growing political, economic and political crisis which was emerging within the new democracies of Europe. Unemployment soared, and families were left bankrupt. In Germany and Austria, armed wings of rival political parties fought out their frustrations on the streets.

Two countries on different sides of the Atlantic again took very different paths out of the crisis. In March 1933 the National Socialists, led by Adolf Hitler, were elected to power in Germany, promising to abandon democracy because of the chaos and unemployment which the crash had caused. Meanwhile in America, Franklin D. Roosevelt took over and launched his New Deal in response to the Great Depression.

As well as financial reform, giant new industrial projects intended for the good of the nation were launched. The infrastructure projects his policies created didn’t just save democracy in the United States by preventing a second civil war; the new railroads, freeways and bridges also provided the means by which the goods of the capitalist economy could eventually spread and flow more efficiently.

As we stand poignantly at a similar fork in the road today, when the top level choices offered become only more binary, one overarching obligation that echoes is the need to save democracy itself. Here politicians and voters would be wise to embrace the brave plans and objectives of a Green New Deal which sprang into mainstream conversation in late 2018.

The Allied victory which ended WWII might have cemented the capitalist route forward that came to dominate the latter half of the 20th century. But it was the World’s Fair in 1939 that first celebrated the full bonding of design and architecture with the twins of consumerism and capital. Hosted in New York, the global expo heralded a future which looked and sounded a lot like utopia. Any doubts as to whether this was achievable were no match for the striking confidence of the heavily marketed scale models on display.

As Curtis explains, what was to come was a future where ‘it’s not that the people are in charge, its that the people’s desires are in charge.’8 Exhibition pieces such as ‘Democracity’ and General Motors’ ‘Futurama’, captured the world’s imagination because they presented a new era in which businesses ‘responded to the innermost desires in a way politicians could never do.’

Long-term stability relied on the promise that the future would always be better than the past. In fact capitalism’s longevity would come to depend on enough people continuing to believe this version of the future over any other. And this was perhaps capitalism’s greatest success. (It was also blessed to thrive through a century in which the world’s natural systems still had some ability to flex.)

A huge explosion in every form of mobility accelerated during the 1950s and 60s, successfully consolidating the 20th century as the age of mass transportation. The West was to be rebranded the ‘free world’, and America’s newly built arteries became known as ‘freeways.’ Capitalism, fuelled largely by the burning of oil, had set every individual free.

It’s worth us noting here that for any movement to succeed, Bob Hunter, co-founder of Greenpeace, will point you to the fundamental importance of storytelling: ‘You have to make a story which travels well. You have to create events which will impact on millions of people in every corner of the world. You have to create a truly global story. And you have to put on a good show.’9 If any movement throughout history has achieved excellence in this realm, then it would be Capitalism.

From the entertainment broadcast on television and radio sets in every family’s home, to the advertising piped directly to people’s neural nodes; from the floating of companies on the stock exchange, the showmanship and flurry of activity every day as the markets closed, to the feature films that further glamourised this lifestyle; from the magazines which promoted the films, to the cleverly placed products which the marketeers needed to sell. And now the social media networks and online retail giants, which through their intimate knowledge of what we already buy, keep bloating our desires with more of the same.

The greatest promo code anyone ever gave capitalism was communism. Like Loki to his brother Thor, communism became the nemesis or arch-rival which only compounded capitalism and made it stronger. During this era, becoming filthy rich became a respected profession in its own right.

During the 1980s Thatcher and Reagan exploited this tense standoff to create a lovechild of their own. Neoliberalism was to become a new ideology which would later work not just as capitalism's powerful defence shield, but also as a leach, draining the system dry from the inside out. Whilst capitalism was a set of social and financial practices whose aim was the accumulation of capital, neoliberalism was a set of beliefs which freed the way to maximise the profits of the capitalists by dismantling the last barriers that had been holding back unaccountable corporate power.

Privatisation, deregulation, the flouting of laws and taxes, the hollowing out of democracies, and the obstruction of green policies – these are all neoliberal trends we are more than familiar with, which together have hamstrung our ability to fight climate change, or plan for our future collective welfare.

Originally capitalism won all previous contests with its rivals, largely because it proved capable of elevating more people out of poverty and hardship than any of the alternatives. Continuing this trend of human alleviation is crucial to building a more sustainable future for the planet overall. Yet these days capitalism’s age is beginning to show, its increasingly worn-out mechanisms creaking ever louder over ever stormier seas, swelled and angered by its own far-reaching oars. Never before has its inner machine work been so transparent, or the darker secrets of its trade had so much scrutiny in the spotlight. As an organism, not only is it continuing to knowingly pollute ecosystems that it relies directly on for its own survival, but it is unapologetically taking from and breaking whole communities too. The ultimate consumer model has begun its final act, of ultimately consuming itself.

In 2010, the researcher Hans Rosling argued in one of his Ted talks, that carbon emissions and sustainable forms of development are intrinsically linked to population growth. A long-term sustainable future relies on us raising the living standards of the world’s poorest, so that we can begin to check population growth by 2050.10 Predictions, however, that on our current course an extra 1.2 million children in the UK alone will fall into poverty by 2030 holds deep irony, proving the capitalist system to which we’re still clinging is categorically no longer fit for purpose.

Thatcher helped set this course during the 1980s when she declared: ‘there is no such thing as society.’ She was of course spinning a pretty obvious falsity, but as we keep finding out to this day, a lie can be an equally effective invention as the truth, and in the hands of those with a tall enough pedestal to preach from, can still set a direction beyond mere discourse.

So the big capitalism truck continues to career down the road, increasingly out of control. There’s now fewer people in the front trying to steer it, and more in the back trying desperately to unload whatever remains of its precious cargo. Meanwhile, with the route still set to the pursuit of infinite growth, the juggernaut just keeps on going, swerving dangerously towards an increasingly perilous cliff-edge of climate (and social) breakdown.

Throughout history empires have fallen when from the outside perspective they have appeared to be at their strongest. From Ancient Rome and Greece to modern-day North America. What the glossy but thin external veneer hides is that they have grown hollow and become rotten from within. Collapsing-empire syndrome, otherwise known as ‘overstretch’, doesn’t just involve an underestimation of resources, but can also include an overreach of ambition and the imagination too. The historian Norman Foster defines this in more human terms as ‘the contest between pride and reality.’11

British journalist George Monbiot once described economic growth as ‘the fairy dust supposed to make all the bad stuff disappear.’12 Yet the fairytales which the capitalist system has been spinning are now so far stretched that they are unravelling at alarming speed. Capitalism will fail sooner or later, ultimately because it drives ecological destruction. It already fails to relieve structural unemployment or soaring inequality, the very things it once did so well – all moral purpose has been lost, whilst ‘the promise of growth is all that’s left.’

As the writer John Higgs explains: ‘If the system the world is run on is made of an imaginary currency underpinned by practices which ultimately harm the very thing we live on, then this system is ultimately on a timer to its own demise.’13 False concepts such as never-ending growth gain strength by surrounding themselves with ideology and elaborate commentaries, in the same way that, as Higgs says, ‘a pearl forms around a piece of grit in an oyster.’ The theory which surrounds any ‘ism’ functions like a ‘sophisticated defence mechanism which protects the central tenets from crashing and burning on the rocks of reality.’14 With a structure such as capitalism, more and more people are beginning to see through the shiny exterior, back to the small lump of dirt, still hidden somewhere in the middle.

This is all very worrying because modern-day economics and the perceived value of money is as much an ecosystem that we rely on for our peaceful prosperity as the daylight, sunshine and the rain. How do we change or reboot a system which we’re already wholly operating within? This is very much our present struggle.

Beginning to discredit some of the darker and more out of control capital flow systems would have only a net positive effect. For whilst carbon emissions remain a significant contributor to global warming, it is the murky world of financial corruption which hides amongst the root causes.15 Noam Chomsky offers an additional starting point when he says we must ‘move from creating structures and institutions which bring out the worst in us to the best.’

One century since capitalism first reigned supreme, today a new generation risks retreating once again into its own self-created empires. Our social media profiles, so carefully curated, they no longer reflect the reality of our daily lives, or more crucially represent how we truly feel. The Hungarian countess Erzie Károlyi said of the early 20th century, ‘to examine fully, with your eyes wide open the world around you, you would have put a lot of other things into question. Your society, everything that surrounds you, and that wasn’t a good thing at that time, because your self-created empire would have very much fallen to bits very much earlier already.’16 Here we are full circle, facing this unique challenge once again. If the jumper was on the wrong way round before, it's now also been turned inside out.

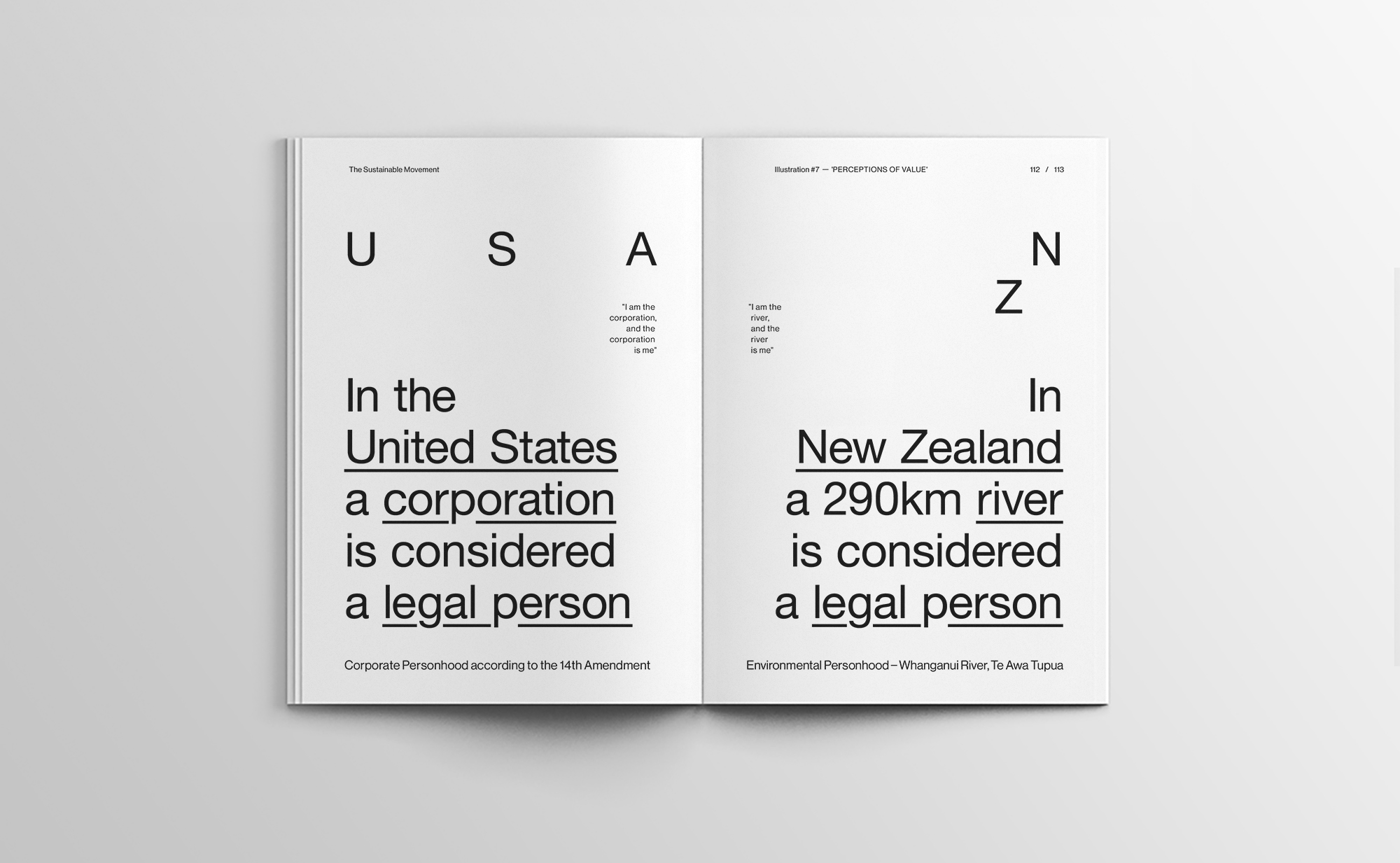

Contrasts – Perceptions of Value

Contrasts – Perceptions of Value—

Credits & Notes

1 / 3 – 8

Adam Curtis

The Century of the Self

BBC Documentary

(2002)

2 / 11 – 12

Norman Stone

World War One – A Short History Penguin Books (2008)

9

Greenpeace

How to Change the World

Film written / directed by Jerry Rothwell

(2015)

10

Hans Rosling

Global population growth, box by box

TED talks (2010)

12

George Monbiot

‘Finally, a breakthrough alternative to growth economics – the doughnut’

The Guardian (10 Apr 2017)

13 – 14

John Higgs

The KLF: Chaos, magic and the band who burned a million pounds

Weidenfeld & Nicolson

(2012)

15

BCSEA

Energy Connections 2017

SFU Centre for Dialogue, Vancouver, BC, Canada

(4 Mar 2017)

16

Adam Curtis

The Century of the Self

BBC Documentary (2002)

Section 1 — Roots

Chapter 1 — An Introduction

Chapter 2 — The Rise and Fall of the Eclectics

Chapter 3 — The Bauhaus Function

Chapter 4 — De Stijl Meets Time

Chapter 5 — The Role of the Magazines

Chapter 6 — DADA

Chapter 7 — War. A Redfinition

Chapter 8 — The Ulm Age of Methods

Chapter 9 — Modernism and the Ongoing Project

Chapter 10 — Capitalism Eats Itself

Chapter 11 — Roughly Where We Stand Now

Interlude — Transition

Section 2 — Leaves

Chapter 12 — How Do Movements Happen?

Chapter 13 — Energy Makes Energy

Chapter 14 — Digital Need Not Be Digital

Chapter 15 — All the Signals of Hope...

Chapter 16 — Defining Sustainabilism

Chapter 17 — Sustainable by Design

Chapter 18 — The Future Will Take Us in Circles

Chapter 19 — Where Do We Go from Here?

Chapter 20 — The Role of the Arts

Chapter 21 — The Value in Meaning

Chapter 22 — Be More Tree

Chapter 23 — An Ending. A Beginning