A 21st Century

Movement

How Do Movements Happen?

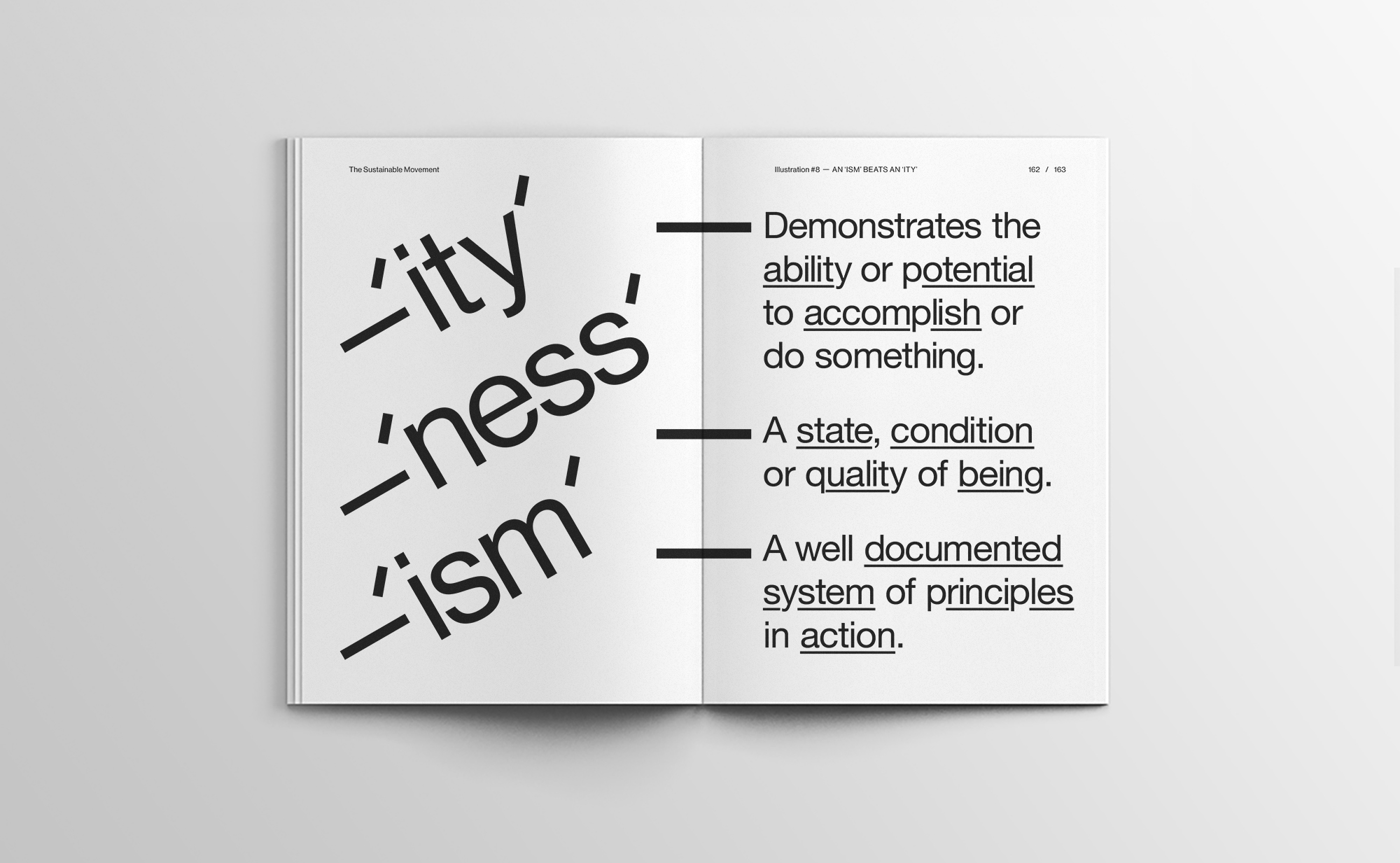

Illustration – An ‘ism’ beats an ‘ity’

Every collective cultural shift in human history is entirely a product of its time. Thus some movements must be content to sit on the shelf for centuries, waiting for just the right circumstances to collide. Not just at the same time, but sometimes in the right sequence too. But how exactly do they begin? And where do they come from? Surely there is more to it than the simple luck of good timing, or the generous help of less quantifiable ingredients which we sometimes call magic.

Breakthroughs in new materials and technologies certainly help change the direction taken by human progress. For example, Modernism in architecture could never have happened without first the mass availability of cheap steel and reinforced concrete, which as the historian Alan Powers explains ‘meant buildings could be lighter, thinner and taller than ever before’1 – during this era, infrastructure for the first time went fully vertical. Yet for the protagonists who were there at the time, from Gropius to Le Corbusier, these artists also point consistently to subtler changes to the collective human ‘spirit’, which seemed to be almost invisibly acting as their guide.

The 1989 ‘summer of rave’ in the UK, which saw London’s clubbers flock to secret locations in farmers’ fields and disused aircraft hangars across the home counties, was only possible because the M25 motorway with its circuitous route around London had been recently completed. An extraordinary British summer which broke all the weather record books certainly helped! But don’t forget Britain’s youth had also been culturally marginalised throughout this entire decade – a time when Stock Aitken & Waterman became ‘the respectable face’ of British pop music at the end of a bitterly divided era under Margaret Thatcher. This famous summer was one of many memorable peaks within the acid house movement, that started in the underground clubs of Chicago during the early 1980s, and ended witnessing the miracle of Chelsea and Spurs fans dancing and hugging in the same farmer’s field.

Breakthroughs in new materials and technologies certainly help change the direction taken by human progress. For example, Modernism in architecture could never have happened without first the mass availability of cheap steel and reinforced concrete, which as the historian Alan Powers explains ‘meant buildings could be lighter, thinner and taller than ever before’1 – during this era, infrastructure for the first time went fully vertical. Yet for the protagonists who were there at the time, from Gropius to Le Corbusier, these artists also point consistently to subtler changes to the collective human ‘spirit’, which seemed to be almost invisibly acting as their guide.

The 1989 ‘summer of rave’ in the UK, which saw London’s clubbers flock to secret locations in farmers’ fields and disused aircraft hangars across the home counties, was only possible because the M25 motorway with its circuitous route around London had been recently completed. An extraordinary British summer which broke all the weather record books certainly helped! But don’t forget Britain’s youth had also been culturally marginalised throughout this entire decade – a time when Stock Aitken & Waterman became ‘the respectable face’ of British pop music at the end of a bitterly divided era under Margaret Thatcher. This famous summer was one of many memorable peaks within the acid house movement, that started in the underground clubs of Chicago during the early 1980s, and ended witnessing the miracle of Chelsea and Spurs fans dancing and hugging in the same farmer’s field.

‘90% of history is being in the right place at the right time’.

—

Bob Hunter

The Greenpeace movement started in Vancouver 1971, partly because at that point in time on the west coast of Canada, they had ‘the biggest concentration of tree huggers, draft dodgers, shift-disturbing unionists, radical students, garbage dump stoppers, freeway fighters, pot smokers, vegetarians, nudists, Buddhists, fish preservationists and back to the landers on the planet’, and to further quote Jerry Rothwell’s documentary, ‘they were all haunted by the spectre of a dead world.’2

One detail that is for certain is that no movement can grow alone in isolation. Sometimes circumstances collide to push united human endeavour in a certain direction. On other occasions new discoveries pull them. But crucially, just the same as with any human-based activity, movements rely on the chance and luck of like-minded groups of people meeting and doing great things together, and throughout history we see many great examples of this.

The British musician Brian Eno is rather fond of the point during the Renaissance when Raphael, Michaelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci were all alive and working in the same city at the same time.3 Likewise, we’ve seen how during the vibrant period of the Bauhaus in Weimar, students were lucky enough to attend the classes of the likes of Gropius, Itten and Schlemmer by day, and then the private classes of progressive heavy-hitters such as Theo van Doesburg by night.

Silicon Valley is of course a contemporary example of this type of hyper-skilled and connected community in action. (Although some might question its motives.) The phenomenon even has a name – Brian Eno likes to call it the talent of the entire scene, or ‘scenius.’ As he explains himself: ‘If genius is the talent of an individual, ‘scenius’ is the talent of a whole community.’4

A Texan photographer by the name of Rex Weyler who was there in Vancouver during the 1970s provides us with another explanation: ‘Change happens where things are mixed up.’5 Today the astounding pace of change isn’t just mixing things up, it’s turning some systems upside down.

Changes to systems which help things like people, information, energy or goods move around more easily have historically been one of the key catalysts that bring forth new ways of thinking in their wake. As culture too (both good and bad) is distributed largely on or through these same systems.Historically, culture, is buoyed by a greater sense of hope or optimism for the future whenever these new systems of travel or communication emerge. The opening of new pathways literally offers us new ways by which to travel, not just physically, but with our minds and imagination too.

Changing popular opinion, however, doesn’t always come easily. During the mid 1990s the Japanese city of Kyoto was not at all ready to accept such an ambitious structure as Hiroshi Hara’s new railway station. The futuristic 15-storey structure of glass and steel was unlike anything Kyoto had ever seen before. Many locals opposed it, saying it was an eyesore completely out of keeping with the city’s predominantly traditional Japanese style.6

Here the progress of aesthetics, and even the functional role of architecture within a community, has often bumped heads with local opinion – you only need to speak to your local planning officer. Nevertheless, Kyoto station was completed and opened to the public in September 1997. Whilst it has kept a few critics, most visitors today react in awe to the giant steel-beamed atrium which hides unassumingly behind the main entrance. With a theatre, museum, sky garden and far-reaching city views, the station has since become a popular tourist attraction in its own right.7

Perhaps this push and pull of attitudes might be one day seen as the dynamo or compressor through which all human creative energy and innovation is generated. Here progression will always be met by opposition (Newton proved this as early as 1687), but the resistance and the rhythm created by all these contradictory forces is at the very heart of how everything culturally lives and breathes. This tension is in fact essential in order to avoid stagnation, and remains where the sparks of change are most likely to occur.

Today we see so many predictions that the future will be this, that or the other, when in fairness, the future will never exist until it is made. Before the future is the future, it is just an idea, a projection, an objective to aim towards. So it is actually here in the present, in the place where all our decisions are currently being processed, which decides what actually takes place next.

Therefore it can sometimes feel like the future appears to come at us more quickly during periods in history where there are great flurries of activity and innovation within the present moment in time. The pace of every idea which we collectively make or realise, represents the perceived speed of our collective footsteps by which we travel through time.

As the Canadian writer Douglas Coupland points out: ‘The future used to be something which was far away, that we were in a sense, never really going to arrive at. But in fact now, we’re already living in the future. Every day yields some kind of new scientific discovery or technological invention that was the stuff of science fiction probably 50 or 60 years ago.’8 Some go as far as to suggest that in just one month of our lifetimes, roughly the same amount of change occurs as happened through the whole of the 14th century.9

So how exactly in the midst of all this craziness can any one of us help steer a cultural movement through such fast and topsy-turvy times? And where does the magic come from which could lead to something as powerful or fundamental as the next Modernist Movement equivalent, and help shape the course of this present century and beyond?

After all, the progression of our own lives tends to be steered more by short-term decisions, largely based on factors relating to the external environment around us. This can include inescapable factors such as family, colleagues, the weather, and economic factors too. These result in largely ‘this-or-that’ choices which are controlled by areas of the brain associated with our ‘willpower.’

It is generally only when we are asked to consider a sequence of events, that we experience more activity in areas of the brain linked to our imagination. Critically, using the imagination parts of the brain more, relies on us having the time and avoiding all the distractions of the this-or-that choices of the now. (Hence why humankind progressed very slowly for some 30-40,000 years or more.)

Cultural movements are sophisticated organisms to realise, because they rely both on the imagining of the long-term vision, along with the planning of all the individual steps required to get the shared idea off the ground. They therefore tend to happen very slowly and organically, and can be prone to stray wildly off course. Hence Modernism fell a long way short of building utopia, and likewise capitalism is producing a lot less ‘happiness machines’ right now.

With new movements still in their infancy, this is where a manifesto or a set of binding principles can be useful. For whilst they are not the map, they can help act as a guide to all the infinite choices which might be encountered on the same shared journey. The process of framing decisions within a wider set of objectives also helps provide direction to any willing protagonist prepared to take a first few steps into the same new thought space.

Here Eno points out: ‘Imagining is possibly the central human trick. That’s what distinguishes us from all other creatures. We can imagine worlds that don’t exist. We cannot only imagine them, we can imagine what is going on within them. We can change details, we can say okay, I’ll make it this instead of that and then see what happens. So we can play out whole scenarios in our heads through our imagination. And that, of course, makes us able to experience empathy, for example.’10

So this is perhaps closer to where the magic comes from – whilst ‘art’ comes from our ability to imagine – magic comes from us having the faith and belief to pursue our actions, even when the circumstances look less than favourable. After all, we can all imagine the impossible, but it is only the magician who can make the impossible happen. In this respect, magic doesn’t come from thin air, but from the willpower area of the mind which fully trusts the imagination to make or create. To quote the English artist Jeremy Deller: ‘Art isn’t about what you make, but about what you make happen.’11

Not all of us are prepared to play in a previously unexplored new territory, because to the unfaithful or inexperienced, it can be an intimidating experience, similar to playing in the dark. Not only is it more lonely in less familiar, dimly lit spaces, but there are also more unforeseens, which we have no previous experience of how to control.

When we live in world where we are bombarded daily with the warnings of dangers all around us, we have become better practised in creating carefully controlled routines instead. So circumstances are more than a little against us when it comes to harnessing, channelling, or even funding this brave pioneering spirit.

The economist E.F. Schumacher once observed that progress often involves ‘tremendous leaps of the imagination into the unknown and unknowable', whilst ‘the leap itself is often taken from only a small platform of observed fact.’12 This is precisely where a fully engaged community can really help. Just like that period during the Renaissance that Eno so admires, collective leaps of culture are often ‘articulated by individuals, but generated by communities.’13

As he reflects, ‘we’re very keen on the names. But what we don’t do is to look at the whole community that they’re drawing from.’14 So, perhaps just like we push forwards with our own footsteps off the security of the sturdy ground beneath our feet, a great cultural leap relies first on a firm footing from within a strong and fully engaged group of like-minded people.

The day a small fishing vessel called the ‘Greenpeace’ set sail for a nuclear test site in the Pacific ocean was no accident. A very unique atmosphere in Vancouver already existed and contributed towards the timing of this brave decision. It just so happened to be Bob Hunter, encouraged and aided by a small group of motivated individuals, who actualised the things which everyone else was already talking about.

This happened somewhere in the sweet spot between human imagination and action, where ‘if you can think of it, you can go out and do it.’ And from here began a chain reaction which made the environmental movement as we know it. To quote Weyler: ‘What Bob said we could do, we did.’15 The nuclear test on Amchitka Island, which they sailed unflinchingly towards, was subsequently delayed, and when it did finally happen, the whole world was watching.

Perhaps it is also worth acknowledging that one of the Greenpeace movement’s founding motivations in 1971 was that through its work and efforts, it would one day become an organisation ‘which no longer needs to exist.’16 Sadly, despite all the very best of intentions, the organisation’s activities are needed now more than ever.

To anyone disheartened by the scale of the challenge that remains for all of us, please take at least some reassurance from one more Schumacher observation: ‘Those that bring forth new ideas are seldom ruled by them.’ To the originators, these ideas are simply the result of their intellectual processes, whilst only in the third and fourth generations do they become the very tools and instruments through which the world is experienced and interpreted.17

This logic explains how a long time ago, the ideas that predominantly came from the Age of Enlightenment ending in 1815, still took another hundred years or more to grow and fully blossom into the diverse creative forces behind 20th-century Modernism. By this same logic, Greenpeace is still a long way off the completion of its chosen task. To quote Robert Macfarlane: ‘Ideas, like waves, have fetches. They arrive with us having travelled vast distances.’18

Perhaps this same theory also explains why today it is a much younger generation of schoolchildren who feel the greatest sense of urgency in fighting climate change and protecting the natural world. Greta Thunberg might have only been 15 years old when she was embraced as an influential spokesperson for the planet, yet she recently demonstrated the ability to cut through the apathy of her parents’ generation in just two small sentences when she said: ‘I don’t want you

to be hopeful. I want you to panic.’19

Humans are blessed with a unique relationship to art which we still perhaps don’t yet fully understand. For example, whilst ‘children learn through play, adults play through art.’20 Ironically, we, as adults (or professionals) tend to use educational or institutional spaces to create safe environments that allow us to continue the ability to play. Here we experiment in controlled conditions, and learn through the process of our ongoing mistakes.

Without the presence of the Bauhaus or HfG Schools, would Modernism’s fingertips have ever stretched so wide? This unique space between play and learning would appear then to be crucial to humankind’s ongoing progression, and should be fostered only when free from the pressures of capital gain.

Successful movements therefore tend to at least start in a vacuum where for a short space of time the elements of fear and financial pressure are completely removed. Perhaps this was one success of the Bauhaus? The school ultimately provided an environment where students from different backgrounds were encouraged not just to explore, but also to relieve their minds of all the preconceptions that risked dampening their imagination. Likewise during the 1970s, Vancouver was still an affordable city for young people, in which they could live and express themselves without the fear of their landlord doubling their rent overnight.

Experimental thought spaces aren’t useful just to the arts – the writer John Higgs points out that ‘mathematicians during the 18th century played around with imaginary numbers for the fun of it and found them to be surprisingly useful. Over time their properties became understood and they became an important tool for engineers. Our understanding of phenomena such as radio waves or electricity is reliant on them.’21 So, as he goes on to suggest: ‘Artists couldn’t create without magical thinking, just as engineers couldn’t work without rational materialism.’22

This is essentially what cultural movements are: simulations played out over the centuries by artists, designers and philosophers. Playing within the boundaries of a set of principles or theories, supported by advances in science and engineering, just to see what quality of fruit the boundaries of their parameters will allow.

All movements tied first to a simple set of binding principles are a form of ‘magical thinking’, because to begin with, these ideas exist only in the minds of the creators. They are incredibly useful for artists and engineers in the things they make, because they provide parameters or a framework to work, play and experiment within. Without these imaginary boundaries, the possibilities quickly become infinite, and any creation would simply lose the ability to be scored or measured, because it fails to meet a clear enough objective.

One detail moving forwards that remains guaranteed, is that within the art of both ‘magic’ and ‘cultural movements’, the actions which ‘prove it’ are more valuable than the idea itself. For example, in the case of a magician holding a hat, the hat is empty until the rabbit is pulled from it – the rabbit does not exist until the magician pulls it from the hat – even if to the magician the rabbit has always existed. This is the same difficulty all artistic and cultural movements face. As Higgs explains, somehow they need to prove the rabbit to the non-believers in order to get them on board.23

So it would seem all models of thinking only work within certain timeframes, and on certain scales. Which is exactly why sometime very soon we must at least try to fully embrace the parameters offered by a movement towards sustainable modes of living. The more fully we explore the potential of this space, the more we will also raise our chances of proving its merits to those who remain in doubt. In turn, the stronger the community we build, the stronger will be the foundations from which we can further leap. A Sustainable Movement has every right to be successful, because as a means of living that helps to get us all from one point in history to the next, far beyond being just a dream, it is also entirely necessary.

One detail that is for certain is that no movement can grow alone in isolation. Sometimes circumstances collide to push united human endeavour in a certain direction. On other occasions new discoveries pull them. But crucially, just the same as with any human-based activity, movements rely on the chance and luck of like-minded groups of people meeting and doing great things together, and throughout history we see many great examples of this.

The British musician Brian Eno is rather fond of the point during the Renaissance when Raphael, Michaelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci were all alive and working in the same city at the same time.3 Likewise, we’ve seen how during the vibrant period of the Bauhaus in Weimar, students were lucky enough to attend the classes of the likes of Gropius, Itten and Schlemmer by day, and then the private classes of progressive heavy-hitters such as Theo van Doesburg by night.

Silicon Valley is of course a contemporary example of this type of hyper-skilled and connected community in action. (Although some might question its motives.) The phenomenon even has a name – Brian Eno likes to call it the talent of the entire scene, or ‘scenius.’ As he explains himself: ‘If genius is the talent of an individual, ‘scenius’ is the talent of a whole community.’4

A Texan photographer by the name of Rex Weyler who was there in Vancouver during the 1970s provides us with another explanation: ‘Change happens where things are mixed up.’5 Today the astounding pace of change isn’t just mixing things up, it’s turning some systems upside down.

Changes to systems which help things like people, information, energy or goods move around more easily have historically been one of the key catalysts that bring forth new ways of thinking in their wake. As culture too (both good and bad) is distributed largely on or through these same systems.Historically, culture, is buoyed by a greater sense of hope or optimism for the future whenever these new systems of travel or communication emerge. The opening of new pathways literally offers us new ways by which to travel, not just physically, but with our minds and imagination too.

Changing popular opinion, however, doesn’t always come easily. During the mid 1990s the Japanese city of Kyoto was not at all ready to accept such an ambitious structure as Hiroshi Hara’s new railway station. The futuristic 15-storey structure of glass and steel was unlike anything Kyoto had ever seen before. Many locals opposed it, saying it was an eyesore completely out of keeping with the city’s predominantly traditional Japanese style.6

Here the progress of aesthetics, and even the functional role of architecture within a community, has often bumped heads with local opinion – you only need to speak to your local planning officer. Nevertheless, Kyoto station was completed and opened to the public in September 1997. Whilst it has kept a few critics, most visitors today react in awe to the giant steel-beamed atrium which hides unassumingly behind the main entrance. With a theatre, museum, sky garden and far-reaching city views, the station has since become a popular tourist attraction in its own right.7

Perhaps this push and pull of attitudes might be one day seen as the dynamo or compressor through which all human creative energy and innovation is generated. Here progression will always be met by opposition (Newton proved this as early as 1687), but the resistance and the rhythm created by all these contradictory forces is at the very heart of how everything culturally lives and breathes. This tension is in fact essential in order to avoid stagnation, and remains where the sparks of change are most likely to occur.

Today we see so many predictions that the future will be this, that or the other, when in fairness, the future will never exist until it is made. Before the future is the future, it is just an idea, a projection, an objective to aim towards. So it is actually here in the present, in the place where all our decisions are currently being processed, which decides what actually takes place next.

Therefore it can sometimes feel like the future appears to come at us more quickly during periods in history where there are great flurries of activity and innovation within the present moment in time. The pace of every idea which we collectively make or realise, represents the perceived speed of our collective footsteps by which we travel through time.

As the Canadian writer Douglas Coupland points out: ‘The future used to be something which was far away, that we were in a sense, never really going to arrive at. But in fact now, we’re already living in the future. Every day yields some kind of new scientific discovery or technological invention that was the stuff of science fiction probably 50 or 60 years ago.’8 Some go as far as to suggest that in just one month of our lifetimes, roughly the same amount of change occurs as happened through the whole of the 14th century.9

So how exactly in the midst of all this craziness can any one of us help steer a cultural movement through such fast and topsy-turvy times? And where does the magic come from which could lead to something as powerful or fundamental as the next Modernist Movement equivalent, and help shape the course of this present century and beyond?

After all, the progression of our own lives tends to be steered more by short-term decisions, largely based on factors relating to the external environment around us. This can include inescapable factors such as family, colleagues, the weather, and economic factors too. These result in largely ‘this-or-that’ choices which are controlled by areas of the brain associated with our ‘willpower.’

It is generally only when we are asked to consider a sequence of events, that we experience more activity in areas of the brain linked to our imagination. Critically, using the imagination parts of the brain more, relies on us having the time and avoiding all the distractions of the this-or-that choices of the now. (Hence why humankind progressed very slowly for some 30-40,000 years or more.)

Cultural movements are sophisticated organisms to realise, because they rely both on the imagining of the long-term vision, along with the planning of all the individual steps required to get the shared idea off the ground. They therefore tend to happen very slowly and organically, and can be prone to stray wildly off course. Hence Modernism fell a long way short of building utopia, and likewise capitalism is producing a lot less ‘happiness machines’ right now.

With new movements still in their infancy, this is where a manifesto or a set of binding principles can be useful. For whilst they are not the map, they can help act as a guide to all the infinite choices which might be encountered on the same shared journey. The process of framing decisions within a wider set of objectives also helps provide direction to any willing protagonist prepared to take a first few steps into the same new thought space.

Here Eno points out: ‘Imagining is possibly the central human trick. That’s what distinguishes us from all other creatures. We can imagine worlds that don’t exist. We cannot only imagine them, we can imagine what is going on within them. We can change details, we can say okay, I’ll make it this instead of that and then see what happens. So we can play out whole scenarios in our heads through our imagination. And that, of course, makes us able to experience empathy, for example.’10

So this is perhaps closer to where the magic comes from – whilst ‘art’ comes from our ability to imagine – magic comes from us having the faith and belief to pursue our actions, even when the circumstances look less than favourable. After all, we can all imagine the impossible, but it is only the magician who can make the impossible happen. In this respect, magic doesn’t come from thin air, but from the willpower area of the mind which fully trusts the imagination to make or create. To quote the English artist Jeremy Deller: ‘Art isn’t about what you make, but about what you make happen.’11

Not all of us are prepared to play in a previously unexplored new territory, because to the unfaithful or inexperienced, it can be an intimidating experience, similar to playing in the dark. Not only is it more lonely in less familiar, dimly lit spaces, but there are also more unforeseens, which we have no previous experience of how to control.

When we live in world where we are bombarded daily with the warnings of dangers all around us, we have become better practised in creating carefully controlled routines instead. So circumstances are more than a little against us when it comes to harnessing, channelling, or even funding this brave pioneering spirit.

The economist E.F. Schumacher once observed that progress often involves ‘tremendous leaps of the imagination into the unknown and unknowable', whilst ‘the leap itself is often taken from only a small platform of observed fact.’12 This is precisely where a fully engaged community can really help. Just like that period during the Renaissance that Eno so admires, collective leaps of culture are often ‘articulated by individuals, but generated by communities.’13

As he reflects, ‘we’re very keen on the names. But what we don’t do is to look at the whole community that they’re drawing from.’14 So, perhaps just like we push forwards with our own footsteps off the security of the sturdy ground beneath our feet, a great cultural leap relies first on a firm footing from within a strong and fully engaged group of like-minded people.

The day a small fishing vessel called the ‘Greenpeace’ set sail for a nuclear test site in the Pacific ocean was no accident. A very unique atmosphere in Vancouver already existed and contributed towards the timing of this brave decision. It just so happened to be Bob Hunter, encouraged and aided by a small group of motivated individuals, who actualised the things which everyone else was already talking about.

This happened somewhere in the sweet spot between human imagination and action, where ‘if you can think of it, you can go out and do it.’ And from here began a chain reaction which made the environmental movement as we know it. To quote Weyler: ‘What Bob said we could do, we did.’15 The nuclear test on Amchitka Island, which they sailed unflinchingly towards, was subsequently delayed, and when it did finally happen, the whole world was watching.

Perhaps it is also worth acknowledging that one of the Greenpeace movement’s founding motivations in 1971 was that through its work and efforts, it would one day become an organisation ‘which no longer needs to exist.’16 Sadly, despite all the very best of intentions, the organisation’s activities are needed now more than ever.

To anyone disheartened by the scale of the challenge that remains for all of us, please take at least some reassurance from one more Schumacher observation: ‘Those that bring forth new ideas are seldom ruled by them.’ To the originators, these ideas are simply the result of their intellectual processes, whilst only in the third and fourth generations do they become the very tools and instruments through which the world is experienced and interpreted.17

This logic explains how a long time ago, the ideas that predominantly came from the Age of Enlightenment ending in 1815, still took another hundred years or more to grow and fully blossom into the diverse creative forces behind 20th-century Modernism. By this same logic, Greenpeace is still a long way off the completion of its chosen task. To quote Robert Macfarlane: ‘Ideas, like waves, have fetches. They arrive with us having travelled vast distances.’18

Perhaps this same theory also explains why today it is a much younger generation of schoolchildren who feel the greatest sense of urgency in fighting climate change and protecting the natural world. Greta Thunberg might have only been 15 years old when she was embraced as an influential spokesperson for the planet, yet she recently demonstrated the ability to cut through the apathy of her parents’ generation in just two small sentences when she said: ‘I don’t want you

to be hopeful. I want you to panic.’19

Humans are blessed with a unique relationship to art which we still perhaps don’t yet fully understand. For example, whilst ‘children learn through play, adults play through art.’20 Ironically, we, as adults (or professionals) tend to use educational or institutional spaces to create safe environments that allow us to continue the ability to play. Here we experiment in controlled conditions, and learn through the process of our ongoing mistakes.

Without the presence of the Bauhaus or HfG Schools, would Modernism’s fingertips have ever stretched so wide? This unique space between play and learning would appear then to be crucial to humankind’s ongoing progression, and should be fostered only when free from the pressures of capital gain.

Successful movements therefore tend to at least start in a vacuum where for a short space of time the elements of fear and financial pressure are completely removed. Perhaps this was one success of the Bauhaus? The school ultimately provided an environment where students from different backgrounds were encouraged not just to explore, but also to relieve their minds of all the preconceptions that risked dampening their imagination. Likewise during the 1970s, Vancouver was still an affordable city for young people, in which they could live and express themselves without the fear of their landlord doubling their rent overnight.

Experimental thought spaces aren’t useful just to the arts – the writer John Higgs points out that ‘mathematicians during the 18th century played around with imaginary numbers for the fun of it and found them to be surprisingly useful. Over time their properties became understood and they became an important tool for engineers. Our understanding of phenomena such as radio waves or electricity is reliant on them.’21 So, as he goes on to suggest: ‘Artists couldn’t create without magical thinking, just as engineers couldn’t work without rational materialism.’22

This is essentially what cultural movements are: simulations played out over the centuries by artists, designers and philosophers. Playing within the boundaries of a set of principles or theories, supported by advances in science and engineering, just to see what quality of fruit the boundaries of their parameters will allow.

All movements tied first to a simple set of binding principles are a form of ‘magical thinking’, because to begin with, these ideas exist only in the minds of the creators. They are incredibly useful for artists and engineers in the things they make, because they provide parameters or a framework to work, play and experiment within. Without these imaginary boundaries, the possibilities quickly become infinite, and any creation would simply lose the ability to be scored or measured, because it fails to meet a clear enough objective.

One detail moving forwards that remains guaranteed, is that within the art of both ‘magic’ and ‘cultural movements’, the actions which ‘prove it’ are more valuable than the idea itself. For example, in the case of a magician holding a hat, the hat is empty until the rabbit is pulled from it – the rabbit does not exist until the magician pulls it from the hat – even if to the magician the rabbit has always existed. This is the same difficulty all artistic and cultural movements face. As Higgs explains, somehow they need to prove the rabbit to the non-believers in order to get them on board.23

So it would seem all models of thinking only work within certain timeframes, and on certain scales. Which is exactly why sometime very soon we must at least try to fully embrace the parameters offered by a movement towards sustainable modes of living. The more fully we explore the potential of this space, the more we will also raise our chances of proving its merits to those who remain in doubt. In turn, the stronger the community we build, the stronger will be the foundations from which we can further leap. A Sustainable Movement has every right to be successful, because as a means of living that helps to get us all from one point in history to the next, far beyond being just a dream, it is also entirely necessary.

—

Credits & Notes

1

Alan Powers

The Modern Movement

in Britain

Merrell Publishers (2005)

2 / 5 / 15

Greenpeace

How to Change the World

Film written / directed by Jerry Rothwell (2015)

3 – 4 / 9 – 10 / 13 – 14 / 20

Brian Eno

John Peel Lecture

BBC Radio 6 (2015)

6 – 7

Michael Lambe

The History of Kyoto Station

Kyoto Transportation Guide

kyotostation.com

8

Jarvis Cocker talks to Douglas Coupland and Shumon Basar

The Age of Earthquakes

BBC Radio 6 (17 Dec 2017)

11

Mary Anne Hobbs talks to Jeremy Deller

Re-imagining Brass

BBC Radio 6 (14 Oct 2017)

12 / 17

E.F. Schumacher

Small Is Beautiful

Vintage Books (2011)

16

D&AD

Brands for the Planet with Greenpeace

Conway Hall (26 Jan 2016)

18

Robert Macfarlane

The Wild Places

Granta Books (2017)

19

Greta Thunberg

‘Schoolgirl climate change warrior – The G2 interview’

The Guardian (11 Mar 2019)

21 – 23

John Higgs

The KLF: Chaos,

magic and the band who burned a million pounds

Weidenfeld & Nicolson (2012)

Section 1 — Roots

Chapter 1 — An Introduction

Chapter 2 — The Rise and Fall of the Eclectics

Chapter 3 — The Bauhaus Function

Chapter 4 — De Stijl Meets Time

Chapter 5 — The Role of the Magazines

Chapter 6 — DADA

Chapter 7 — War. A Redfinition

Chapter 8 — The Ulm Age of Methods

Chapter 9 — Modernism and the Ongoing Project

Chapter 10 — Capitalism Eats Itself

Chapter 11 — Roughly Where We Stand Now

Interlude — Transition

Section 2 — Leaves

Chapter 12 — How Do Movements Happen?

Chapter 13 — Energy Makes Energy

Chapter 14 — Digital Need Not Be Digital

Chapter 15 — All the Signals of Hope...

Chapter 16 — Defining Sustainabilism

Chapter 17 — Sustainable by Design

Chapter 18 — The Future Will Take Us in Circles

Chapter 19 — Where Do We Go from Here?

Chapter 20 — The Role of the Arts

Chapter 21 — The Value in Meaning

Chapter 22 — Be More Tree

Chapter 23 — An Ending. A Beginning