A 21st Century

Movement

Digital Need Not Be Digital

‘The machine allowed precision (in representation), it totally changed the way we built buildings, and the way we composed art. They began to mimmic and form rhythms with each other’.

—

Doris Wintgens Hötte

—

Doris Wintgens Hötte

The age of the computer and the internet is already giving way to the beginnings of a new era of machine learning and artificial intelligence. Data now allows us new forms of precision, similar to the boundaries once broken by the mechanical machine. It too can totally change the way we build buildings, the way we distribute commodities, workers or energy, and the way we compose art. All these elements are starting to mimic and form rhythms with each other, so much so that at times it can feel as though we’re beginning to make ourselves a redundant part of the puzzle.

By 2020 there will be 300 times as much information available as we had in 2005.1 Accelerating computational power and enhanced connectivity are at the heart of what some are calling the ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution.’ Number four shows all the signs of being very different from the last, where the previously dominant drivers of change – globalisation, technology and ‘financialisation’ – served us well by typically delivering the double bonus of economic growth and social progress.

However, as these three drivers have accelerated together, a widely acknowledged disparity has opened between economic growth and social progress, putting both people and the planet under substantial strain. Underpinned by rapid advances in technologies including artificial intelligence, robotics, the internet of things, nanotechnology and biotechnology (to name but a few), ‘disruption’ is now the new norm.2

So today, whilst there is no shortage of ‘technical innovation’, we do drastically need to innovate on what we think of as ‘innovation.’ The Digital Revolution, whilst undeniably groundbreaking in changing the way we communicate, network and share, has arguably under-delivered thus far in some of the basics of how we live. This is partly because so many givens of the natural world’s systems fall completely outside of the digital sphere. Nature after all is a closed loop system. Basic human requirements too, such as water, food, sleep, love and shelter, exist largely outside of technology’s full reach.

The economist E.F. Schumacher wrote: ‘The true problems of living – in politics, economics, education, marriage, etc. – are always problems of overcoming or reconciling opposites. They are divergent problems and have no solution in the ordinary sense of the word. They demand of us not merely the employment of’ our ‘reasoning powers but the commitment of’ our ‘whole personality.’3 Here, much to some people’s disappointment, technology can be little more than a distraction or a means of escape.

Thus far, there has been a problem in the relationship between the Digital Revolution and the Green one. The two have yet to become entirely compatible, or to intertwine in such a way that they find a way of mutually benefitting one another. The primary link between the two is of course the human, who exists somewhere between each of these realms. We make this relationship complex by committing, as Schumacher says, the entire human personality.

These two entities will only become more interdependent, as the practices we use to manage the natural world will increasingly rely on information digitally harvested and shared. You could think of these two interdependencies a little like the left and right sides of the human brain, which work together allowing us to perform and complete basic tasks. If we manage to connect the two in the right way, they will empower not just ourselves, but also the natural environment surrounding us, allowing both to thrive. Similarly, when we fail to make the right connections, we will continue to misfire, sometimes on an epic planetary scale.

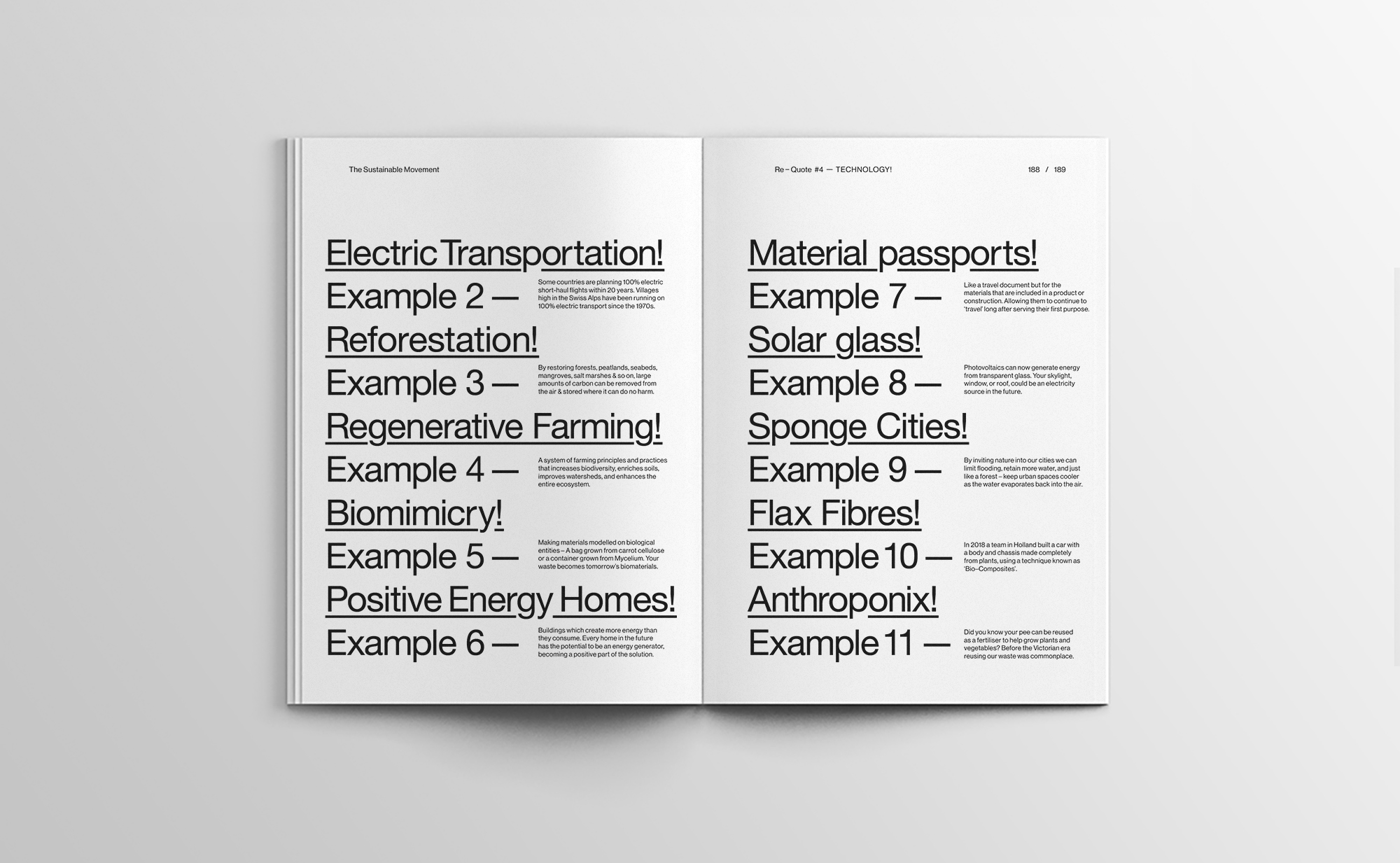

Danny Hillis, an inventor, scientist, author and engineer explains: ‘Technology is the name we give to something when it doesn’t work properly yet.’4 The use of this label is then more than a little worrying considering a recurring belief throughout human history has been that ‘technology will save us.’ Silicon Valley has most recently tried respinning this flawed but still popular myth, and a financial climate led largely by speculation allows this fiction to flourish. Meanwhile, back down here in reality, technology will never ‘save us’, but the ideas and actions born from it one day just might.

Brian Eno points out that only once something reaches the stage where it has a name, such as a ‘bicycle’ or a ‘grand piano’, do we tend to no longer think of these things as ‘technology.’5 Likewise, only at this stage do these inventions truly enrich our lives. The real breakthroughs, that stay with us for centuries are then in fact the resulting applications, not the new technologies. But if we were to value technology this way around, how would the financial services sector make money gambling over things once they are proven?

Another weakness in our relationship with technology crops up when we rely on the computer as a machine to foretell or even create the future for us – in much the same way as ancient leaders once trusted their oracles. So much so that around 500 BC the oracle at Delphi became known as the ‘belly button’ of the Ancient Greek world. (This visual cue might remind you of Stanley Kubrick’s visualisation of Hal in 2001: A Space Odyssey.)

Whilst the computer deals explicitly in quantities, the ancient oracles dealt predominantly in qualities. And both can fail dramatically through their own limitations, or equally by how their prophesies are interpreted by us mere mortals. In 560 BC, Croesus, King of Lydia, consulted the Delphic oracle before attacking Persia, and according to the Greek historian Herodotus was advised: ‘If you cross the river, a great empire will be destroyed.’6 Believing the response to be favourable, Croesus attacked, whilst of course it was his own empire that was ultimately sacked by the Persians. As a Wikipedia entry notes, ‘any inconsistencies between prophecies and events were dismissed as a failure to correctly interpret the responses, not as an error of the oracle.’

We can sometimes be just as guilty of interpreting and skewing data in much the same way. Invariably we look first for data that reinforces the assumptions we’ve already made. Data with the highest perceived value in today’s society is primarily geared to demonstrate how systems can be exploited, monetised, or made more efficient for capital gains. The interests of humanity, community, well-being, or nature barely get a look-in.

The writer Douglas Coupland calls this the new era of ‘Data Capitalism’ whereby we ourselves are the ones being harvested, for our tastes, loves, fears, shoe sizes, friendship connections, and even our weirdest fetishes.7 Our personal information is gathered, processed, commodified, and then sold back to us. ‘We’re being fracked,’ casually observed Jarvis Cocker, as the two chatted together in December 2018.8 Unless we somehow manage to change our perceptions of value, in this dystopian future, humans become a primary resource.

This is because to capitalists, data is a resource, just like oil, gas or coal. It is a commodity to exploit and sell, and a means by which companies become rich and powerful. Controlling and protecting the flow of data is now at the heart of any future trade negotiation, because a vast array of profit-making schemes depend on its free movement. According to the writer Ben Tarnoff: ‘The flow of data now contributes more to world GDP than the flow of physical goods. In other words, there’s more money in moving information across borders than in moving soybeans and refrigerators.’9

From an entirely different perspective, and to the benefit of the Sustainable Movement, data becomes instead an essential element – much like the earth, water, the wind or the sun. Because without data, there is no means of establishing whether a process has become fully sustainable or not. Here on the brighter side of seeing, data becomes something we simply cannot function without.

It was the Ancient Greeks who originally came up with the concept of the ‘four elements’ of fire, earth, air and water, proposed originally to explain the make-up of all matter in terms of simpler substances. Eastern faith systems point to a very similar collection of ingredients, with some, including Buddhism, also recognising the critical importance of the void. The space between elements being of course an incredibly valuable tool in its own right, and one which designers make use of all the time. Scientists more recently suggest about 25 common elements are found in all living things. (Meanwhile breakthroughs in DNA sequencing are further changing our ideas of how everything is connected.)

In none of these theories about the make-up of living things does code, artificial intelligence or data yet play any active role. Yet for future life on Earth to continue to exist and become sustainably protected, it is entirely plausible that they one day might. In fact, sustainable methods of living require measurement and analysis by default, because without mathematical proof, there is simply no trustworthy means of validation.

Until this time, words like ‘sustainable’ will remain the empty labels we already use, unless we harness data to act on a functional level, as a clear method of verification. Here free-flowing data will increasingly play a holistic role in measuring the impacts to which any system also interlinks. Data thus might one day become our sixth essential element. Or perhaps, if you’re a scientist, the 26th common element.

Data’s usefulness to the Sustainable Movement lies in its ability to help businesses understand and act on the environmental impacts of their operations. And by making their activity more transparent, it then follows by steering customers to make more informed decisions as well.

Data helps us assess and calculate environmental risks. It guides our understanding of where the future demands for energy and food will appear, and where the biggest gaps in efforts to reduce carbon emissions remain. It can propel the optimisation of how we use resources, reducing waste and saving money. In the long-term, data helps governments implement policy and better regulation – an area where they presently struggle to keep pace.10 Data, then, allows us to do a great deal. If we wish to reduce wastefulness or learn more about how our ecological footprint applies across all our systems of living, data will ultimately help us to track, keep on track, and optimise.

In the case of climate change, there is no shortage of data to prove it is real, but there are still fundamental problems with how this information is interpreted and acted upon. These problems exist as issues of human complexities, or the choices between where we perceive there to be the most value; and these problems will continue to exist unless we can summon the willpower needed to make suitable enough new tools, or as Eno says, ‘the resulting applications.’

In 1951 Alan Turing (the mathematician and computer scientist who cracked the Nazi encryption code), developed mathematical equations to help us understand the formation of patterns and shapes in biological organisms. Essentially he used maths to explain why leopards grew spots, whilst zebras had stripes. If this was possible 80 years ago, imagine the problems we could use maths and modern computing power to help us understand and solve today.

Traditionally we measure the success of our systems by the axes of cost and time, with a view to increasing efficiency and advancing financial profit. Tomorrow’s measurement tools will need to make much more complex calculations, which allow us to calculate the full environmental implications of whole systems and connected processes, over many lifecycles. Their axes might end up being varied and many.

So a more sustainable future will rely on the creation of new standards of measurement and new concepts of value. These standards will need to be easy to grasp by people from all cultures and flexible in their application. Here the free flow of information relies not just on the refinement of how it flows, but the organisation of the information itself.

If the Digital Revolution has taught us one thing thus far, it’s that the world can live and breathe with collective human emotion. Following tragedies in places as far apart as Paris, London, Istanbul, Kabul, and most recently Christchurch, we’ve found sympathy and grief does outpour over social media in holistic connectivity. Meanwhile the same technology has helped us meet and congregate en masse in the real world too.

In 2011 the Occupy movement, a small protest that began in New York, quickly spread to a mass movement in over 1000 towns and cities worldwide. Perhaps this next phase can deliver on this next level, an altogether bigger promise – the successful application of global collaboration working to civil, societal and environmental needs.

One divergent problem to be aware of is that the more technology disrupts people’s daily lives, their means of employment, financial or personal security, the less it may be trusted in other aspects of what it is asked to deliver. Technology was supposed to ‘bring people together.’ We’ve seen in some ways that it has, whilst in other instances, it is also capable of causing large fractures. But don’t forget, ‘bringing people together’ – this was never technology’s explicit aim, it was only the promise.

The computer machine’s short-sightedness has always been humankind’s kryptonite too. Our short-term needs have for too long overshadowed the longer-term requirements of future generations. For a machine at least, this is because to predict the future it has to make its calculations based on data that already exists. Calculations are made ‘based on the implicit assumption that “the future is already here”, that it exists in a determinate form.’11 The machine predicts the future by analysing the present and comparing it to events in the past. As a result, we become stuck with the system within which we already exist.

The solution of course lies not in trying to predict the future, but in making it instead. Almost a half century ago, back in 1973, Schumacher already predicted: ‘We must look for a revolution in technology to give us inventions and machines which reverse the destructive trends now threatening us all.’12 This involves first and foremost a revolution in how we think, and in where we place our priorities.

Amazon recently announced it was working on a pet translator that would sit around your dog’s neck, and by the process of machine learning, it would increasingly recognise your pet’s movements and noises, in order to learn what it wanted, then translate these signs back to the owner using the human voice. Whilst this might well be amusing and novel to consumers, we would perhaps be better off building something like this, but big enough to wrap around planet Earth, and then listen more closely to what it has to say.

Technology will only ever be as successful or accountable as the explicit objectives that it is designed to fulfil. This is why this next phase will need to be defined by a new wave of progressive thinkers exploiting technology for everyone’s benefits. And meanwhile, the format of using technology as a means to exploit each other, would be the most preferable of 20th-century schemes to leave well and truly behind.

Like any relationship, the better the two-way communication (or essentially the flow of information), the more we increase the chance of a successful partnership. This will only come as we create meaningful and truly useful technology.

To be explicit, the aim should not be to make technology smarter, the aim should be to enable and empower smarter and more caring people instead. Neither ‘digital’ nor ‘technology’ should be anyone’s future end goal; they are simply a means by which we achieve a healthier and more enriched life here in the present. Technologists this century who aren’t also thinking in terms of the original organic elements of life, will fall short of solving human needs, just as drastically as environmentalists who once retreated from civilisation, whilst ignoring the inordinate possibilities offered by the arrival of the computer.

Fully connecting sustainable processes serving a global population of eight billion would simply not have been possible in a pre-internet age. Because the management of data interlinking people, processes, systems and their environmental footprint, on a truly global scale, relies on a network of networks. Since Tim Berners Lee very kindly plugged us all in together at the end of the 1980s, we’ve had this basic application for some time already. The only real question that remains amongst all the choices of what we build next, is what exactly are we waiting for?

By 2020 there will be 300 times as much information available as we had in 2005.1 Accelerating computational power and enhanced connectivity are at the heart of what some are calling the ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution.’ Number four shows all the signs of being very different from the last, where the previously dominant drivers of change – globalisation, technology and ‘financialisation’ – served us well by typically delivering the double bonus of economic growth and social progress.

However, as these three drivers have accelerated together, a widely acknowledged disparity has opened between economic growth and social progress, putting both people and the planet under substantial strain. Underpinned by rapid advances in technologies including artificial intelligence, robotics, the internet of things, nanotechnology and biotechnology (to name but a few), ‘disruption’ is now the new norm.2

So today, whilst there is no shortage of ‘technical innovation’, we do drastically need to innovate on what we think of as ‘innovation.’ The Digital Revolution, whilst undeniably groundbreaking in changing the way we communicate, network and share, has arguably under-delivered thus far in some of the basics of how we live. This is partly because so many givens of the natural world’s systems fall completely outside of the digital sphere. Nature after all is a closed loop system. Basic human requirements too, such as water, food, sleep, love and shelter, exist largely outside of technology’s full reach.

The economist E.F. Schumacher wrote: ‘The true problems of living – in politics, economics, education, marriage, etc. – are always problems of overcoming or reconciling opposites. They are divergent problems and have no solution in the ordinary sense of the word. They demand of us not merely the employment of’ our ‘reasoning powers but the commitment of’ our ‘whole personality.’3 Here, much to some people’s disappointment, technology can be little more than a distraction or a means of escape.

Thus far, there has been a problem in the relationship between the Digital Revolution and the Green one. The two have yet to become entirely compatible, or to intertwine in such a way that they find a way of mutually benefitting one another. The primary link between the two is of course the human, who exists somewhere between each of these realms. We make this relationship complex by committing, as Schumacher says, the entire human personality.

These two entities will only become more interdependent, as the practices we use to manage the natural world will increasingly rely on information digitally harvested and shared. You could think of these two interdependencies a little like the left and right sides of the human brain, which work together allowing us to perform and complete basic tasks. If we manage to connect the two in the right way, they will empower not just ourselves, but also the natural environment surrounding us, allowing both to thrive. Similarly, when we fail to make the right connections, we will continue to misfire, sometimes on an epic planetary scale.

Danny Hillis, an inventor, scientist, author and engineer explains: ‘Technology is the name we give to something when it doesn’t work properly yet.’4 The use of this label is then more than a little worrying considering a recurring belief throughout human history has been that ‘technology will save us.’ Silicon Valley has most recently tried respinning this flawed but still popular myth, and a financial climate led largely by speculation allows this fiction to flourish. Meanwhile, back down here in reality, technology will never ‘save us’, but the ideas and actions born from it one day just might.

Brian Eno points out that only once something reaches the stage where it has a name, such as a ‘bicycle’ or a ‘grand piano’, do we tend to no longer think of these things as ‘technology.’5 Likewise, only at this stage do these inventions truly enrich our lives. The real breakthroughs, that stay with us for centuries are then in fact the resulting applications, not the new technologies. But if we were to value technology this way around, how would the financial services sector make money gambling over things once they are proven?

Another weakness in our relationship with technology crops up when we rely on the computer as a machine to foretell or even create the future for us – in much the same way as ancient leaders once trusted their oracles. So much so that around 500 BC the oracle at Delphi became known as the ‘belly button’ of the Ancient Greek world. (This visual cue might remind you of Stanley Kubrick’s visualisation of Hal in 2001: A Space Odyssey.)

Whilst the computer deals explicitly in quantities, the ancient oracles dealt predominantly in qualities. And both can fail dramatically through their own limitations, or equally by how their prophesies are interpreted by us mere mortals. In 560 BC, Croesus, King of Lydia, consulted the Delphic oracle before attacking Persia, and according to the Greek historian Herodotus was advised: ‘If you cross the river, a great empire will be destroyed.’6 Believing the response to be favourable, Croesus attacked, whilst of course it was his own empire that was ultimately sacked by the Persians. As a Wikipedia entry notes, ‘any inconsistencies between prophecies and events were dismissed as a failure to correctly interpret the responses, not as an error of the oracle.’

We can sometimes be just as guilty of interpreting and skewing data in much the same way. Invariably we look first for data that reinforces the assumptions we’ve already made. Data with the highest perceived value in today’s society is primarily geared to demonstrate how systems can be exploited, monetised, or made more efficient for capital gains. The interests of humanity, community, well-being, or nature barely get a look-in.

The writer Douglas Coupland calls this the new era of ‘Data Capitalism’ whereby we ourselves are the ones being harvested, for our tastes, loves, fears, shoe sizes, friendship connections, and even our weirdest fetishes.7 Our personal information is gathered, processed, commodified, and then sold back to us. ‘We’re being fracked,’ casually observed Jarvis Cocker, as the two chatted together in December 2018.8 Unless we somehow manage to change our perceptions of value, in this dystopian future, humans become a primary resource.

This is because to capitalists, data is a resource, just like oil, gas or coal. It is a commodity to exploit and sell, and a means by which companies become rich and powerful. Controlling and protecting the flow of data is now at the heart of any future trade negotiation, because a vast array of profit-making schemes depend on its free movement. According to the writer Ben Tarnoff: ‘The flow of data now contributes more to world GDP than the flow of physical goods. In other words, there’s more money in moving information across borders than in moving soybeans and refrigerators.’9

From an entirely different perspective, and to the benefit of the Sustainable Movement, data becomes instead an essential element – much like the earth, water, the wind or the sun. Because without data, there is no means of establishing whether a process has become fully sustainable or not. Here on the brighter side of seeing, data becomes something we simply cannot function without.

It was the Ancient Greeks who originally came up with the concept of the ‘four elements’ of fire, earth, air and water, proposed originally to explain the make-up of all matter in terms of simpler substances. Eastern faith systems point to a very similar collection of ingredients, with some, including Buddhism, also recognising the critical importance of the void. The space between elements being of course an incredibly valuable tool in its own right, and one which designers make use of all the time. Scientists more recently suggest about 25 common elements are found in all living things. (Meanwhile breakthroughs in DNA sequencing are further changing our ideas of how everything is connected.)

In none of these theories about the make-up of living things does code, artificial intelligence or data yet play any active role. Yet for future life on Earth to continue to exist and become sustainably protected, it is entirely plausible that they one day might. In fact, sustainable methods of living require measurement and analysis by default, because without mathematical proof, there is simply no trustworthy means of validation.

Until this time, words like ‘sustainable’ will remain the empty labels we already use, unless we harness data to act on a functional level, as a clear method of verification. Here free-flowing data will increasingly play a holistic role in measuring the impacts to which any system also interlinks. Data thus might one day become our sixth essential element. Or perhaps, if you’re a scientist, the 26th common element.

Data’s usefulness to the Sustainable Movement lies in its ability to help businesses understand and act on the environmental impacts of their operations. And by making their activity more transparent, it then follows by steering customers to make more informed decisions as well.

Data helps us assess and calculate environmental risks. It guides our understanding of where the future demands for energy and food will appear, and where the biggest gaps in efforts to reduce carbon emissions remain. It can propel the optimisation of how we use resources, reducing waste and saving money. In the long-term, data helps governments implement policy and better regulation – an area where they presently struggle to keep pace.10 Data, then, allows us to do a great deal. If we wish to reduce wastefulness or learn more about how our ecological footprint applies across all our systems of living, data will ultimately help us to track, keep on track, and optimise.

In the case of climate change, there is no shortage of data to prove it is real, but there are still fundamental problems with how this information is interpreted and acted upon. These problems exist as issues of human complexities, or the choices between where we perceive there to be the most value; and these problems will continue to exist unless we can summon the willpower needed to make suitable enough new tools, or as Eno says, ‘the resulting applications.’

In 1951 Alan Turing (the mathematician and computer scientist who cracked the Nazi encryption code), developed mathematical equations to help us understand the formation of patterns and shapes in biological organisms. Essentially he used maths to explain why leopards grew spots, whilst zebras had stripes. If this was possible 80 years ago, imagine the problems we could use maths and modern computing power to help us understand and solve today.

Traditionally we measure the success of our systems by the axes of cost and time, with a view to increasing efficiency and advancing financial profit. Tomorrow’s measurement tools will need to make much more complex calculations, which allow us to calculate the full environmental implications of whole systems and connected processes, over many lifecycles. Their axes might end up being varied and many.

So a more sustainable future will rely on the creation of new standards of measurement and new concepts of value. These standards will need to be easy to grasp by people from all cultures and flexible in their application. Here the free flow of information relies not just on the refinement of how it flows, but the organisation of the information itself.

If the Digital Revolution has taught us one thing thus far, it’s that the world can live and breathe with collective human emotion. Following tragedies in places as far apart as Paris, London, Istanbul, Kabul, and most recently Christchurch, we’ve found sympathy and grief does outpour over social media in holistic connectivity. Meanwhile the same technology has helped us meet and congregate en masse in the real world too.

In 2011 the Occupy movement, a small protest that began in New York, quickly spread to a mass movement in over 1000 towns and cities worldwide. Perhaps this next phase can deliver on this next level, an altogether bigger promise – the successful application of global collaboration working to civil, societal and environmental needs.

One divergent problem to be aware of is that the more technology disrupts people’s daily lives, their means of employment, financial or personal security, the less it may be trusted in other aspects of what it is asked to deliver. Technology was supposed to ‘bring people together.’ We’ve seen in some ways that it has, whilst in other instances, it is also capable of causing large fractures. But don’t forget, ‘bringing people together’ – this was never technology’s explicit aim, it was only the promise.

The computer machine’s short-sightedness has always been humankind’s kryptonite too. Our short-term needs have for too long overshadowed the longer-term requirements of future generations. For a machine at least, this is because to predict the future it has to make its calculations based on data that already exists. Calculations are made ‘based on the implicit assumption that “the future is already here”, that it exists in a determinate form.’11 The machine predicts the future by analysing the present and comparing it to events in the past. As a result, we become stuck with the system within which we already exist.

The solution of course lies not in trying to predict the future, but in making it instead. Almost a half century ago, back in 1973, Schumacher already predicted: ‘We must look for a revolution in technology to give us inventions and machines which reverse the destructive trends now threatening us all.’12 This involves first and foremost a revolution in how we think, and in where we place our priorities.

Amazon recently announced it was working on a pet translator that would sit around your dog’s neck, and by the process of machine learning, it would increasingly recognise your pet’s movements and noises, in order to learn what it wanted, then translate these signs back to the owner using the human voice. Whilst this might well be amusing and novel to consumers, we would perhaps be better off building something like this, but big enough to wrap around planet Earth, and then listen more closely to what it has to say.

Technology will only ever be as successful or accountable as the explicit objectives that it is designed to fulfil. This is why this next phase will need to be defined by a new wave of progressive thinkers exploiting technology for everyone’s benefits. And meanwhile, the format of using technology as a means to exploit each other, would be the most preferable of 20th-century schemes to leave well and truly behind.

Like any relationship, the better the two-way communication (or essentially the flow of information), the more we increase the chance of a successful partnership. This will only come as we create meaningful and truly useful technology.

To be explicit, the aim should not be to make technology smarter, the aim should be to enable and empower smarter and more caring people instead. Neither ‘digital’ nor ‘technology’ should be anyone’s future end goal; they are simply a means by which we achieve a healthier and more enriched life here in the present. Technologists this century who aren’t also thinking in terms of the original organic elements of life, will fall short of solving human needs, just as drastically as environmentalists who once retreated from civilisation, whilst ignoring the inordinate possibilities offered by the arrival of the computer.

Fully connecting sustainable processes serving a global population of eight billion would simply not have been possible in a pre-internet age. Because the management of data interlinking people, processes, systems and their environmental footprint, on a truly global scale, relies on a network of networks. Since Tim Berners Lee very kindly plugged us all in together at the end of the 1980s, we’ve had this basic application for some time already. The only real question that remains amongst all the choices of what we build next, is what exactly are we waiting for?

Next ︎

Chapter 15 —

All the signals of Hope are already out there blinking and flashing – In Action!

Chapter 15 —

All the signals of Hope are already out there blinking and flashing – In Action!

—

Credits & Notes:

1 / 10

Saurabh Tyagi

‘What Does Big Data Mean For Sustainability?’

sustainablebrands.com

(24 Jan 2017)

2

Dr Celine Herweijer et al

‘Enabling a sustainable Fourth Industrial Revolution’

PwC (2017)

3

E.F. Schumacher

Small Is Beautiful

Vintage Books (2011)

4 – 5

Brian Eno

John Peel Lecture

BBC Radio 6 (2015)

6

Wikipedia Page

‘Oracle’, wikipedia.org

7 – 8

Jarvis Cocker talks to Douglas Coupland

and Shumon Basar

The Age of Earthquakes

BBC Radio 6 (17 Dec 2017)

9

Ben Tarnoff

‘Data is the new lifeblood of capitalism’

The Guardian (01 Feb 2018)

11

Adam Curtis

HyperNormalisation

BBC Documentary (2017)

12

E.F. Schumacher

Small Is Beautiful

Vintage Books (2011)

Section 1 — Roots

Chapter 1 — An Introduction

Chapter 2 — The Rise and Fall of the Eclectics

Chapter 3 — The Bauhaus Function

Chapter 4 — De Stijl Meets Time

Chapter 5 — The Role of the Magazines

Chapter 6 — DADA

Chapter 7 — War. A Redfinition

Chapter 8 — The Ulm Age of Methods

Chapter 9 — Modernism and the Ongoing Project

Chapter 10 — Capitalism Eats Itself

Chapter 11 — Roughly Where We Stand Now

Interlude — Transition

Section 2 — Leaves

Chapter 12 — How Do Movements Happen?

Chapter 13 — Energy Makes Energy

Chapter 14 — Digital Need Not Be Digital

Chapter 15 — All the Signals of Hope...

Chapter 16 — Defining Sustainabilism

Chapter 17 — Sustainable by Design

Chapter 18 — The Future Will Take Us in Circles

Chapter 19 — Where Do We Go from Here?

Chapter 20 — The Role of the Arts

Chapter 21 — The Value in Meaning

Chapter 22 — Be More Tree

Chapter 23 — An Ending. A Beginning